Science Nugget: ‘Sun’day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter Science nuggets that shed light on some of our star’s mysteries - Solar Orbiter

'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

(Solar Orbiter Nugget #50 by M. Janvier1 and D. Trotta2 )

Introduction

Almost two years ago, and after a year since the start of the nominal science phase, we introduced the Solar Orbiter science nuggets to the solar and space science communities. These are short articles based on a topic related to the use of Solar Orbiter data and answering some of the fundamental questions in solar and space physics. These nuggets are proposed on the model of Hugh Hudson’s Yohkoh, then Rhessi, and now Solarnuggets (see footnotes*).

To celebrate our 50th nugget (or rather, an ‘ingot’ based on all the contributed nuggets…), we revisited hereafter the many contributions to various science topics provided by this vibrant community.

Heating of the Sun’s atmosphere

Our first nugget contribution (Nugget #1) provided a review of one of the key early results from the mission, namely the identification of EUV small-scale brightenings referred to as ‘campfires’, extending their spatial range at an even smaller scale than earlier thought, with high resolution imaging provided by the Extreme UV Imager on board the mission. While these brightenings could be evidence of plasma cooling through the instrument temperature response, coordinated observations with Solar Dynamics Observatory/AIA and with the spectrometer on board Solar Orbiter, Nugget #6 and Nugget #43 showed that some of these EUI brightenings barely reach coronal temperatures, and that, at least in the samples analysed, the emissions mainly came from transition region temperatures. Then, more analyses will be needed to understand whether these brightenings are indeed related to coronal heating in various regions of the Sun.

In the meantime, the coronal heating processes were revisited in Nugget #22, as the spatial scale provided by EUV high resolution imager on board Solar Orbiter revealed no evidence of a role for large-scale/observable reconnection, and may point to a steadily heating process acting over long periods of time and at very small scales not observed yet. Steady processes such as decayless oscillations in coronal loops were investigated in Nugget #15, providing evidence that the energy is taken from quasi-steady plasma flows, and could be a part of heating the coronal plasma.

The importance of high resolution and combination of multiple diagnostics such as photospheric magnetic field measurements and spectroscopy are crucial to understand how the corona is structured, as demonstrated in Nugget #14 and Nugget #18. The former showed how thermal non equilibrium and instabilities shape the morphology and variability of coronal structures, while the latter focused on the quiet Sun, and found that there is an intricate magnetic coupling between the photosphere and the corona that plays a role in structuring the plasma loops in the quiet-Sun corona.

Fig 1: Nuggets have investigated 'campfires' (a, b), coronal loop oscillations (c) as well as coronal rain (d)

Origins of the Solar Wind

With its instruments and elliptical orbits, Solar Orbiter provides the capability to answer one other fundamental question, that is the understanding of the sources of the solar wind(s). The first science perihelion and coordinated observations with other space missions provided some clues, such as providing evidences of the S-web model (a model describing a network filling the corona, of narrow open field corridors bounded by a web of high magnetic field connectivity change surfaces). In Nugget #11, the authors interpreted Doppler maps of open field line corridors obtained with the Hinode spacecraft, and in situ measurements from Solar Orbiter. The power of coordinated observations both from in situ and remote-sensing was also shown in Nugget #35, where the authors showed how the variability of the solar wind could be mapped to the crossing of different regions of the Sun, in particular of a coronal hole/active region complex.

Obtaining the elemental abundance of the solar plasma both at its sources and in the detected solar wind is a powerful tool to understand its nature. To do so, understanding the fractionation of plasma in different structures is important, as was shown in Nugget #34. There, the authors showed that sulfur, which has an intermediate first ionisation potential, is an important element as it behaves differently depending on the coronal structures (open or closed field lines) considered, therefore providing a stronger proxy to locate the sources of the solar wind. Composition within the solar wind was investigated in Nugget #38, where mesoscale periodic structures detected in the heavy ion composition observed by Solar Orbiter was found to be consistent with the observed plasma originating from an active region.

Combining in situ measurements and diagnostics of the extended corona is made possible with Solar Orbiter. First, coronagraphic imagery combined with Doppler dimming techniques provides a means of obtaining information on outward flow velocities, as well as mass flux, as a function of height above the solar limb as presented in Nugget #7. Such coronagraphic imagery can also be combined with in situ measurements, such as what was done during a coordination with Parker Solar Probe that saw the spacecraft in the Solar Orbiter coronagraph field of view. With both remote-sensing and in situ observations and analytical modelling, the rate of energy deposition in the corona was estimated in Nugget #20.

Fig 2: Multi instruments observations are tackling the sources of the solar wind, from the S-web (a) to active region/coronal hole complex (b), as well as linking the plasma composition at the Sun (c) and in situ (d)

Flares, Coronal Mass Ejections and space weather

X-ray diagnostics are necessary to understand where the energy is released during energetic events such as solar flares. Such diagnostics have shown a good agreement with the standard flare model, in that the locations of non-thermal sources agree with the predictions given by the model, as shown in Nugget #13 for the footpoints of an eruptive filament, or with the first joint analysis of microflares with NuSTAR (Nugget #48). However, other observations such as the enhanced soft X-ray emissions detected before the onset of the flare impulsive phase (discussed in Nugget #5), or the role of 3D structures in the energy release process leading to pulsations phenomena (also observed in microwave, as shown in Nugget #28) and overall drifting sources (Nugget #24) call for a more complete model taking into account the temporal and spatial evolution of the (pre-) flaring region. Finally, a statistical analysis showed that hard microflares are rooted in sunspots (Nugget #39), which calls for a better characterisation of the relation between strong magnetic fields and electron acceleration mechanisms.

Fig 3: X-ray spectroscopy confirms the standard flare model picture (a, b), although more work is necessary to understand the relation with quasi-period pulsations (c) and the magnetic field intensity (d)

Solar flares, especially of the highest classes, are often accompanied by coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Remote observations of CMEs are routinely associated with three distinct regions of emission, namely a bright leading edge of highly ionized plasma, a low-density magnetically dominated cavity, and an embedded dense cold core associated with a solar prominence. While the latter is generally hard to identify in situ, Solar Orbiter provides an advancement to previous datasets (Nugget #4), while its heliospheric imager provides exquisite details of CME structures, as demonstrated in Nugget #9. CMEs are crucial players for potentially hazardous space weather phenomena, and are particularly hard to predict both in terms of the arrival time to Earth and the potential damage they can cause. Solar Orbiter's low latency data products can be used to provide real time information about the magnetic field in the solar wind, especially for Earth observation purposes with on the Sun-Earth line, as shown in Nugget #29. While our prediction capabilities continue to grow, efforts need to be continued to improve the modeling of the magnetic structures of interplanetary CMEs: in Nugget #37, detection of an interplanetary CME with both Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter shows that the propagation processes (and even CME-CME interaction, that can create pairs of interplanetary shocks, as shown in Nugget #47) need to be taken into account to better constrain such models. On the other hand, Solar Orbiter heliospheric imagery capability is an important asset to reconstruct the 3D CME trajectory when taking into account other data with SOHO/LASCO and STEREO/SECCHI (Nugget #30) and more generally, it also provides a powerful constraint in calibrating far-side helioseismic maps that can then be used to detect and predict the evolution of active regions that can induce space weather events when rotating towards Earth (Nugget #8).

Fig 4: Research on CME propagation and their internal sub-structures (such as shocks, a) are aided by multi spacecraft observaitons (b)

Fundamental constituents and mechanisms governing the Solar Wind

Solar Orbiter shed new light on how wave-particle interaction works in the heliosphere, a fundamental problem as most of the observable universe is in a state of collisionless plasma. Nugget #3 focused on a statistical study of Langmuir waves, which are electrostatic waves with frequencies close to the local electron plasma frequency that are believed to play a fundamental role in solar wind electron thermodynamics. Here, the authors found that they tend to occur more frequently where local enhancement in plasma density and depression in magnetic fields are present (so called “magnetic holes”). Langmuir waves are often associated with beams of energetic electrons of solar origin which can, in turn, be modified by wave-particle interactions. Nugget #31 compared the in-situ electron spectra and the wave activity, and showed that the electron spectra are indeed shaped by Langmuir wave growth in the deca-keV range.

At lower energies, the solar wind electrons are routinely observed in three families with different velocity signatures. The core, representing the thermal electrons at low energies; the halo population at higher energies; the strahl, i.e., a beam of high-energy electrons that follows the magnetic field lines. How these populations are shaped and evolve in interplanetary space is poorly understood. Solar Orbiter was used in conjunction with Parker Solar Probe in Nugget #33 where the authors showed that the strahl electrons seem to lose coherence as they propagate away from the Sun, likely due to wave particle interaction with high frequency “whistler” waves.

A key feature of the complex, collisionless solar wind is the possibility to create ion distributions that are far from local thermodynamic equilibrium. This is the case for ubiquitous proton beams that can be investigated with Solar Orbiter high-quality measurements. Nugget #16 found that such beams are not strictly parallel to the local magnetic field as expected, but exhibit an intriguing feature of non-field-alignment, influencing significantly the growth of wavelike turbulence at ion scales.

The nature of such turbulent fluctuations in relation with complex particle distributions in both protons and alpha particles was also investigated, with particular focus on the association between the emergence of coherent events of turbulence with small-scale features of ion velocity distributions, elucidating possible pathways to effective energy dissipation (Nugget #26). Employing machine learning techniques, protons and alpha particles populations and their kinetic behaviour could be studied with exquisite level of detail, important to investigate both the origin of such solar wind populations and their role in solar wind heating, acceleration and expansion (Nugget #40). Finally, Solar Orbiter was exploited to test different scenarios of solar wind expansion which depend on the solar source region, key to explain its acceleration in the solar atmosphere (Nugget #44).

Fig 5: In situ observations in the solar wind allow us to probe fine scale structures such as vortices and current sheets (a), or understand in finer details the particle-wave interactions (b) as well as particles velocity signatures (c)

Particle Acceleration in the heliosphere

Solar Orbiter provides the possibility to study interplanetary shocks driven by solar eruptions with unprecedented levels of detail, thus enabling the discovery of many unconstrained particle acceleration mechanisms. Nugget #10 investigates one of these events, where rarely observed structures, known as shocklets, have been found upstream of an IP shock and measured by multiple spacecraft for the first time. Shocklets play a role in energising particles efficiently to high energies as they precondition the plasma before it encounters the shock.

Interplanetary shocks are often associated with efficient ion acceleration, and are known to enhance energetic particle fluxes (so-called Energetic Storm Particle (ESP) events). In an effort analysing two ESP events, Nugget #25 showed that several features of the particle fluxes and spectra can be attributed to the properties of turbulence upstream of the shock, which effectively hinders the escape of lower-energy particles from the shock. While in-situ electron acceleration at interplanetary shocks remains elusive as rare and/or generating from small “hotspots” on the shock surface, a relativistic electron beam due to in-situ shock acceleration was identified, producing insights into its governing acceleration mechanisms (Nugget #27).

Solar energetic particle (SEP) events are studied intensively since they can fill the inner solar system with ionizing radiation. In Nugget #12, the authors found that events rich in 3He can arise in multiple situations in the corona and are widespread, providing insights into the essential features of the acceleration mechanisms (emerging flux, reconnection) as opposed to other phenomena that are not actually required (X-ray flares, active region eruptions). Further, it was shown how Solar Orbiter introduced transformational innovation in the quality of such 3He events, in particular for the analysis of heavy and ultra heavy ions, for example suggesting a common acceleration mechanism between 3He and Fe (Nugget #42). Some other SEP events call for a better understanding of their propagation, as shown in an unusual SEP event where the presence of an interplanetary flux rope is believe to play a role in an unusual long path lengths (Nugget #17).

Finally, several detections of solar energetic electrons made with Solar Orbiter and other heliospheric observers provided a big enough sample to probe into their spatial distribution in the inner heliosphere (Nugget #2): the resulting scaling law is an important constraint to model their propagations away from the Sun. Solar Orbiter has also remarkable capabilities to observe the radio emission produced as a consequence of accelerated electrons, as shown by the first characterisation of type III burst decays in the 3-13 MHz range (Nugget #41).

Fig 6: Detection of high-energy particles can investigated to understand their distribution of and ultimately their acceleration processes (a), refine studies of elemental composition of these beams (b) as well as relate to mechanisms happening at the Sun (c).

The importance of coordinated observations

We finish our 'tour' of contributions by highlighting the importance of multi viewpoints of the same phenomena occurring at and near the Sun, and dedicated coordinated observations such as with ground-based observations (an example of a successful ground-based observations campaign with the Swedish Solar Telescope is given in Nugget #36).

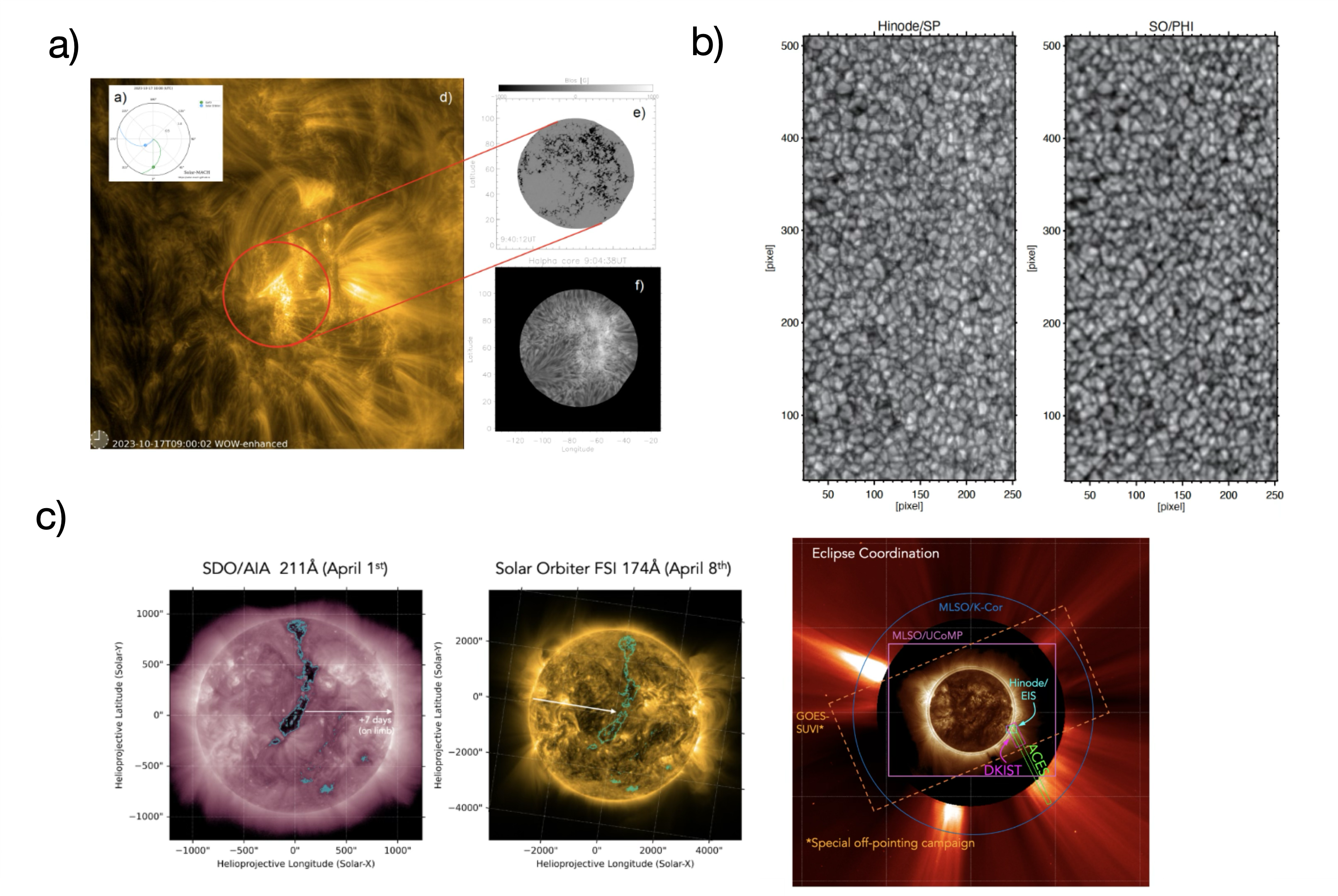

Such efforts provide stereoscopic views of the same phenomena observed with different assets, which help: inferring the correct properties of the photospheric magnetic field (the so-called ambiguity problem, tackled in Nugget #21) or disentangling the Doppler velocity parameters with multiple viewpoints to understand velocity fields in solar granulation Nugget #49) with both Solar Orbiter and Hinode, understanding the energy interplay between the flaring region and their CME counterparts during occulted events, a condition necessary to look at high altitude X-rays sources (Nugget #46 with Solar Orbiter and ASO-S), combine photospheric magnetic field measurements with coronal and coronagraphy imagery to understand the role of small filaments during eruptions (Nugget #19 with Solar Orbiter, SDO and STEREO-A), or understand the relation between CMEs and EUV waves due to events seen in quadrature with different spacecraft (Solar Orbiter and STEREO-A, Nugget #23). A coordination made during the 2024 total solar eclipse (Nugget #32) provided augmented multiwavelengths datasets including DKIST and the ACES experiment, with in situ data with both Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe. Such coordinated observations can be repeated in future total solar eclipse opportunities such as in the summer 2026.

Fig 7: Solar Orbiter coordinates observations with ground-based observatories (a), as well as space assets (b). Recently, a total solar eclipse campaign (c) allowed researchers to follow structures seen in different the different fields of view of multiple assets.

Conclusion

Solar Orbiter science nuggets are only a small sample of all the various results already obtained since the launch of the mission, but showcase the various topics tackled with the datasets obtained by the spacecraft and the instruments on board. Furthermore, multi heliospheric observers, as well as near and on Earth assets (e.g. ground-based observatories) provide unique opportunities with Solar Orbiter to gather data needed to answer some of the fundamental questions of solar and space physics. We invite the readers to a more in depth look at the results obtained with Solar Orbiter with the updated bibliography as well as the recent published paper on the early science results [1].

As we celebrate all these contributions, we also point out to a major milestone: Solar Orbiter has now entered its high latitude science phase, after a successful Venus Gravity Assist Manoeuvre that took place on 18 February 2025 (such manoeuvre allows for some interesting Venusian science too, as showcased in Nugget #45). For the first time in March and April, Solar Orbiter will take humanity’s first images of the Sun south, then north poles. As such, we look forward to more exciting science made by the community and invite all to contribute to future nuggets.

[1] Solar Orbiter: a short review of the mission and early science results by L. Harra and D. Müller, ASS 2025 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10509-025-04400-3

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the contributions from the nuggets writers, as well as the instrumental, operational, and scientific teams that have made the collection of all datasets used in different studies available along with their in-depth analyses.

Affiliations

1 European Space Agency, ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands

2 European Space Agency, ESAC, Villanueva de la Canada, Spain

* In Hugh Hudson’s definition, “a nugget is a lump, especially of native gold or other precious metal. [The science articles, originally the Yohkoh’s science notes] are nuggets, in the sense that they have a rough exterior, but they have a precious substance beneath the surface.” Variations now exist for other missions (e.g. IRIS nugget, MIST nugget )

Nuggets archive

2025

19/03/2025: Radial dependence of solar energetic particle peak fluxes and fluences

12/03/2025: Analysis of solar eruptions deflecting in the low corona

05/03/2025: Propagation of particles inside a magnetic cloud: Solar Orbiter insights

19/02/2025: Rotation motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

12/02/2025: 'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

22/01/2025: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

15/01/2025: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

2024

18/12/2024: Shocks in tandem : Solar Orbiter observes a fully formed forward-reverse shock pair in the inner heliosphere

11/12/2024: High-energy insights from an escaping coronal mass ejection

04/12/2024: Investigation of Venus plasma tail using the Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe and Bepi Colombo flybys

27/11/2024: Testing the Flux Expansion Factor – Solar Wind Speed Relation with Solar Orbiter data

20/11/2024:The role of small scale EUV brightenings in the quiet Sun coronal heating

13/11/2024: Improved Insights from the Suprathermal Ion Spectrograph on Solar Orbiter

30/10/2024: Temporally resolved Type III solar radio bursts in the frequency range 3-13 MHz

23/10/2024: Resolving proton and alpha beams for improved understanding of plasma kinetics: SWA-PAS observations

25/09/2024: All microflares that accelerate electrons to high-energies are rooted in sunspots

25/09/2024: Connecting Solar Orbiter and L1 measurements of mesoscale solar wind structures to their coronal source using the Adapt-WSA model

18/09/2024: Modelling the global structure of a coronal mass ejection observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe

28/08/2024: Coordinated observations with the Swedish 1m Solar Telescope and Solar Orbiter

21/08/2024: Multi-source connectivity drives heliospheric solar wind variability

14/08/2024: Composition Mosaics from March 2022

19/06/2024: Coordinated Coronal and Heliospheric Observations During the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse

22/05/2024: Real time space weather prediction with Solar Orbiter

15/05/2024: Hard X ray and microwave pulsations: a signature of the flare energy release process

01/02/2024: Relativistic electrons accelerated by an interplanetary shock wave

11/01/2024: Modelling Two Consecutive Energetic Storm Particle Events observed by Solar Orbiter

2023

14/12/2023: Understanding STIX hard X-ray source motions using field extrapolations

16/11/2023: EUI data reveal a "steady" mode of coronal heating

09/11/2023: A new solution to the ambiguity problem

02/11/2023: Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe jointly take a step forward in understanding coronal heating

25/10/2023: Observations of mini coronal dimmings caused by small-scale eruptions in the quiet Sun

18/10/2023: Fleeting small-scale surface magnetic fields build the quiet-Sun corona

27/09/2023: Solar Orbiter reveals non-field-aligned solar wind proton beams and its role in wave growth activities

20/09/2023: Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops

23/08/2023: A sharp EUI and SPICE look into the EUV variability and fine-scale structure associated with coronal rain

02/08/2023: Solar Flare Hard Xrays from the anchor points of an eruptive filament

28/06/2023: 3He-rich solar energetic particle events observed close to the Sun on Solar Orbiter

14/06/2023: Observational Evidence of S-web Source of Slow Solar Wind

31/05/2023: An interesting interplanetary shock

24/05/2023: High-resolution imaging of coronal mass ejections from SoloHI

17/05/2023: Direct assessment of far-side helioseismology using SO/PHI magnetograms

10/05/2023: Measuring the nascent solar wind outflow velocities via the doppler dimming technique

26/04/2023: Imaging and spectroscopic observations of EUV brightenings using SPICE and EUI on board Solar Orbiter

19/04/2023: Hot X-ray onset observations in solar flares with Solar Orbiter/STIX

12/04/2023: Multi-scale structure and composition of ICME prominence material from the Solar Wind Analyser suite

22/03/2023: Langmuir waves associated with magnetic holes in the solar wind

15/03/2023: Radial dependence of the peak intensity of solar energetic electron events in the inner heliosphere

08/03/2023: New insights about EUV brightenings in the quiet sun corona from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

Sign in

Sign in

Science & Technology

Science & Technology