Science Nugget: Assessment of the near Sun axial magnetic field of the 10 March 2022 CME observed by Solar Orbiter from active region helicity budget - Solar Orbiter

Assessment of the near-Sun axial magnetic field of the 10 March 2022 CME observed by Solar Orbiter from active region helicity budget

(Solar Orbiter Nugget #52 by S. Koya1,2, S. Patsourakos1, M. K Georgoulis3,4, and A. Nindos1)

1. Introduction

Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) are energetic eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields from the solar atmosphere [1,2,3]. Understanding the near-Sun magnetic field strength of CMEs is crucial as it plays a key role in shaping the early evolution of CME dynamics and their potential geoeffectiveness. However, there are no routine, continuous observations of near-Sun CME magnetic fields. In [4], a method based on the magnetic helicity of the CME was introduced, which can be indirectly used to estimate the near-Sun magnetic field of the CMEs. The overarching principle for this assessment is the conservation of magnetic helicity accumulated in an Active Region (AR) and transferred to CMEs upon launch. By following the methodology proposed by [4] with a more refined estimation of the helicity budget of the CME, we estimated the near-Sun magnetic field of a CME observed on 10 March 2022 by Solar Orbiter, STEREO, SOHO and SDO. This study provided us with an enhanced understanding of the event and its magnetic field evolution with heliocentric distance.

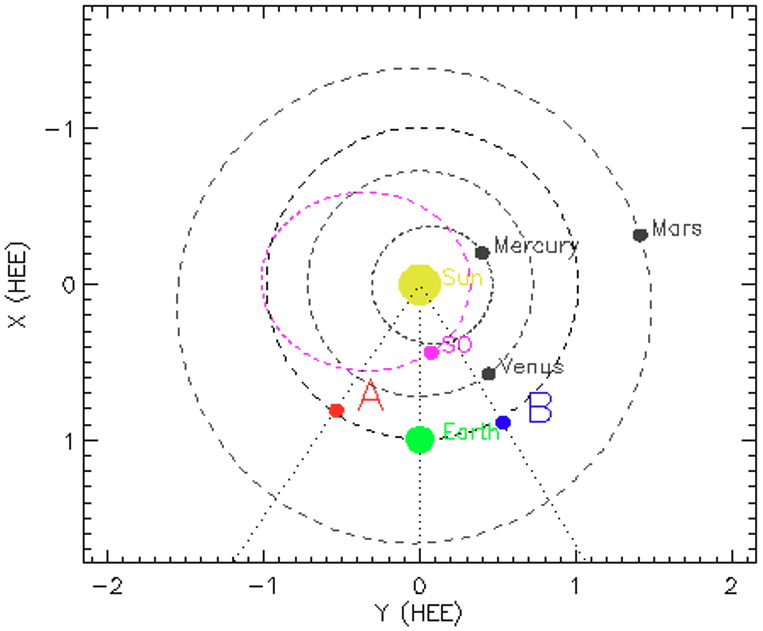

Figure 1. Spacecraft configuration of STEREO-B (blue circle), STEREO-A (red circle), SolO (magenta circle), Bepi Colombo (orange circle), Earth (green circle) and Sun (yellow) on 10 March 2022 at 00:00 UT in heliocentric Earth ecliptic (HEE) system. The dotted lines show the angular difference between STEREO A and B from the Sun-Earth line. Units are in AU.

2. Methodology

We estimated a CME’s near-Sun axial magnetic field that erupted from AR 12962 on 10 March 2022. This event was observed from an advantageous spacecraft configuration with Solar Orbiter (SolO), located just 7.8 degrees east of the Sun-Earth line at a heliocentric distance of 0.43 AU, in good alignment with it and the L1 measurements by the WIND spacecraft at 0.99 AU (See Fig.1) . We followed the methodology of [4] to estimate the near-Sun axial magnetic field of the CME. First, we tracked the temporal evolution of the instantaneous relative magnetic helicity of the CME’s source AR, NOAA AR 12962, using a nonlinear force-free, magnetic connectivity-based (CB) method [5], that revealed a significant decrease in the helicity budget of the AR prior to the CME eruption. Next, we determined a set of CME geometrical parameters (e.g., radius R, length L) from forward-modelling geometrical fits of multi-view coronal observations, utilising data from the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory/Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph Experiment (SOHO/LASCO) and the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory/Sun-Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation (STEREO/SECCHI) coronagraphs. For this, we applied the Graduated Cylindrical Shell (GCS) model [6]. We then estimated the near-Sun axial magnetic field of the CME at 0.03 AU and its maximum height by employing the Lundquist flux rope model [7]. Assuming a power-law index variation for the magnetic field with heliocentric distance, we estimated a best-fit single power-law index by incorporating the estimated near-Sun magnetic field at 0.03 AU and magnetic-field measurements at 0.43 AU and 0.99 AU.

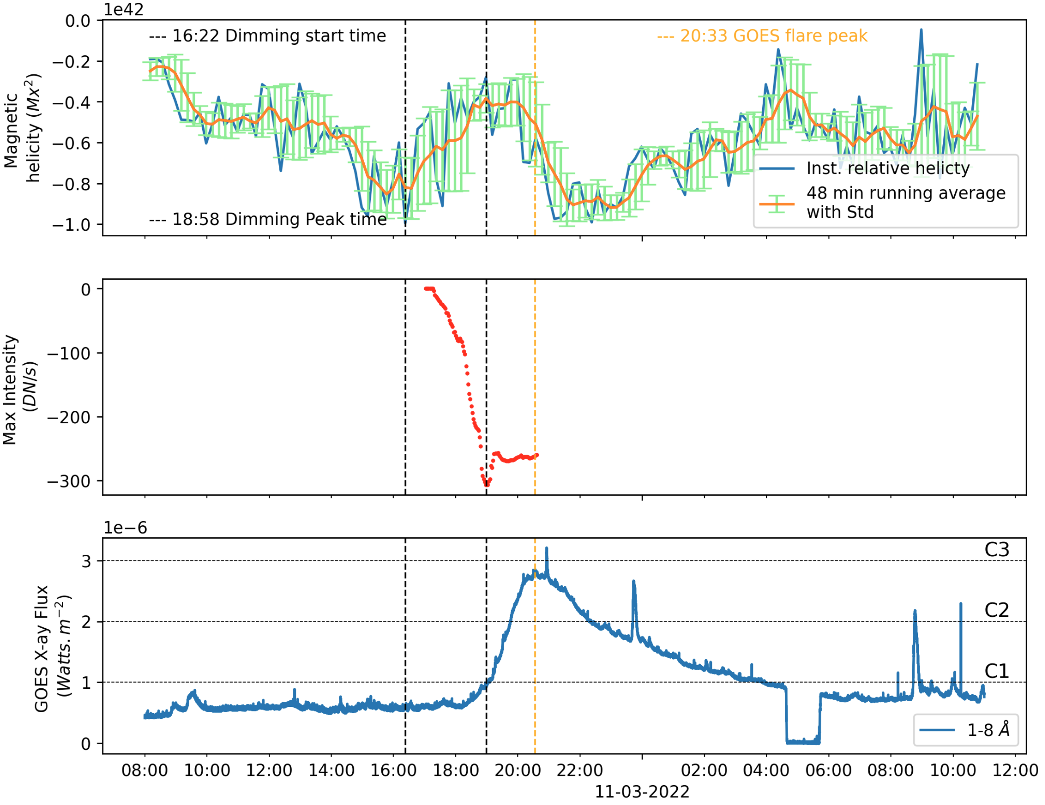

Figure 2. Top to bottom: a) Temporal evolution of magnetic properties of NOAA AR 12962. The blue curve represents the instantaneous values of the relative magnetic helicity estimated from the CB method. The over-plotted orange curve and green error bars are the running averages of the estimated values over a 48-minute window, with standard deviation, , respectively. b) Red dots represent the base difference intensity of the darkest region within the dimming. c) The blue curve represents GOES 1 – 8 Å X-ray flux 1-minute data. In all panels, vertically dashed black lines indicate the dimming start and peak time, and the orange dashed line represents the GOES flare peak time.

3. Results

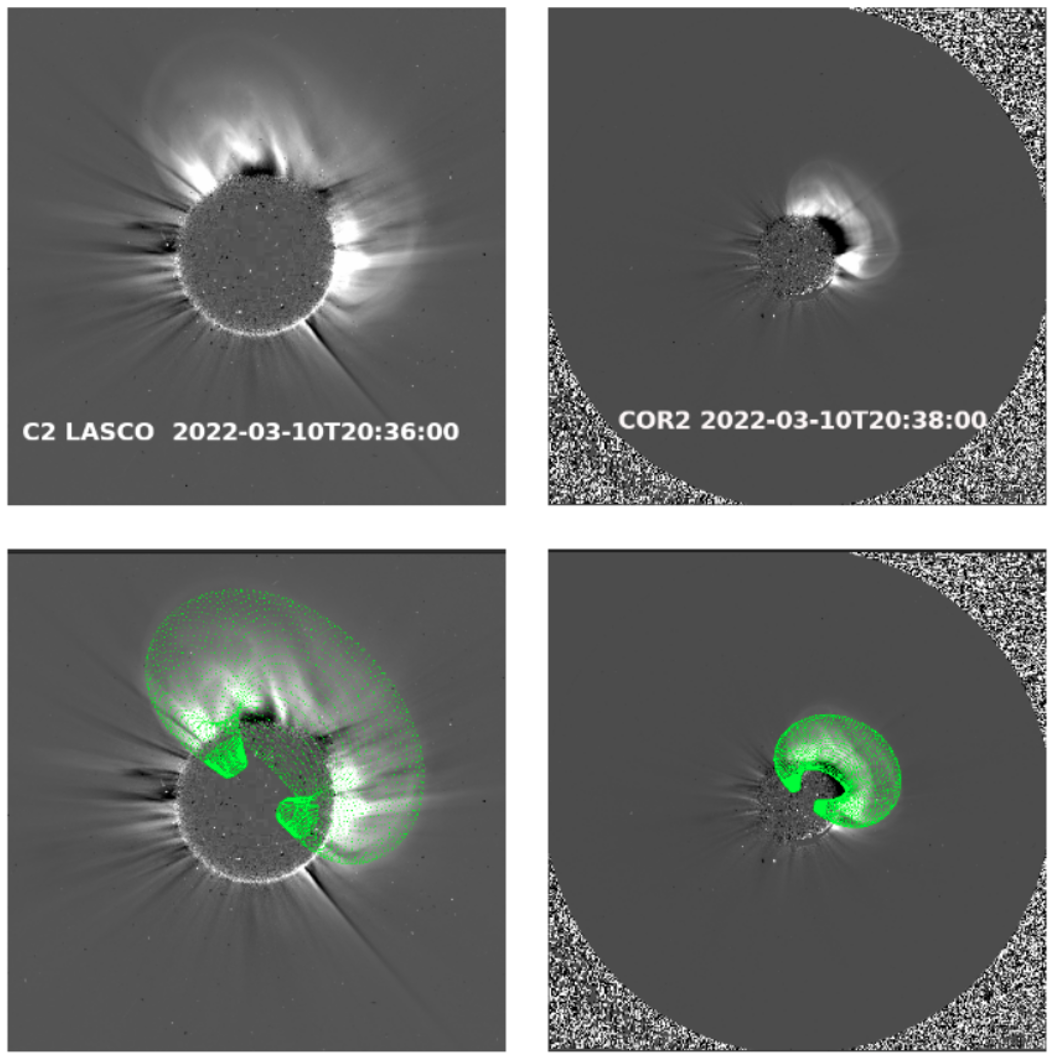

We tracked the temporal evolution of the instantaneous relative magnetic helicity of the source AR of the CME. The net helicity difference between the pre- and post-eruption phase in the AR was estimated as (−7.1 ± 1.2) × 1041 Mx2 (see Fig 2), which is assumed to be bodily transported to the CME. Assuming a Lundquist flux-rope model and geometrical parameters obtained through the GCS CME forward modelling (see Fig.3), we determined the CME axial magnetic field at a GCS-fitted height of 7.6 R⊙ (0.03 AU) as 2067 ± 405 nT.

Figure 3. GCS model fits of the 10 March 2022 CME. Top row: Images of the CME taken by LASCO/C2/SOHO (left) and SECCHI COR2/STEREO-A (right). Bottom row: The same images, with the GCS wireframe overlaid.

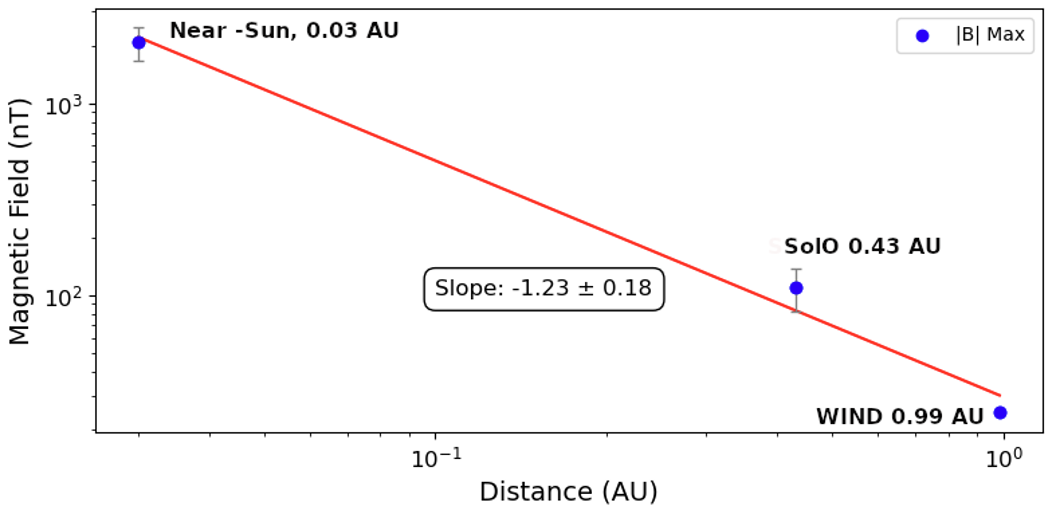

Assuming a power-law variation of the magnetic field with distance, we estimated a single power-law index of −1.23 ± 0.18 from 0.03 AU to L1 (see Fig.4). While there have been studies in this direction, mainly focused on the inner heliospheric region from 0.3 AU to 1 AU, our study offers a distinct perspective by estimating a single power-law index of −1.23 ± 0.18, incorporating data points from near-Sun to 0.43 AU and up to 0.99 AU. Our findings indicate a less steep decline in the magnetic field strength with distance compared to previous studies. However, they align with studies including near-Sun in situ magnetic field measurements, such as from the Parker Solar Probe [8,9].

Figure 4. CME magnetic field variation with distance. Blue points with error bars depict the maximum magnetic field B0 and its uncertainties, respectively.The near- Sun field is estimated from the application of our methodology, while the fields at 0.43 AU (Solar Orbiter) and 0.99 AU (WIND) stem from in-situ measurements. The 0.99 AU measurements have minimal error (on the order pT), and the red line represents the least-squares best fit of the CME magnetic field at the respective three locations.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this study not only estimates the near-Sun magnetic field of the CME and enhances understanding of the power-law variation of the CME magnetic field with heliocentric distance but also confirms that differences in pre- and post-eruptive helicity in source ARs can be explored to study the resulting CME. The availability of multiple viewpoints and co-aligned observations of CME events enables the development of a database to determine a maximum likelihood near-Sun CME magnetic field based on observations rather than models. Our methodology offers a foundation for routine calculations of magnetic helicity in the lower solar atmosphere, complementing existing geometric models of CMEs in the outer corona.

Creating a near-Sun CME axial magnetic filed database and our approach could contribute to a more systematic understanding of magnetic field evolution of the CME. Additionally, the maximum likelihood values of near-Sun CME axial magnetic filed and insights into its variation with heliocentric distance could serve as initial conditions for inner helospheric CME propagation such as the European Heliospheric FORecasting Information Asset (EUHFORIA) model [10].

For further reading, see full publication Koya et al. (2024).

Affiliations

(1) Section of Astrogeophysics, Department of Physics, University of Ioannina, 45110 Greece

(2) Institute of Physics, University of M. Curie-Skłodowska, Pl. M. Curie-Skłodowskiej 1, 20-031 Lublin, Poland

(3) Space Exploration Sector, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723, USA

(4) Research Center for Astronomy and Applied Mathematics, Academy of Athens, 11527 Athens, Greece

References

[6] Thernisien, A. F. R., Howard, R. A., & Vourlidas, A. 2006, ApJ, 652, 763

[7] Lundquist, S. (1950). Magnetohydrostatic fields. Ark. Fys., 2:361–365.

[11] Pomoell, J., & Poedts, S. 2018, J. Space Weather Space Clim., 8, A35

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the SWATNet project funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 955620.

Nuggets archive

2025

19/03/2025: Radial dependence of solar energetic particle peak fluxes and fluences

12/03/2025: Analysis of solar eruptions deflecting in the low corona

05/03/2025: Propagation of particles inside a magnetic cloud: Solar Orbiter insights

19/02/2025: Rotation motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

12/02/2025: 'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

22/01/2025: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

15/01/2025: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

2024

18/12/2024: Shocks in tandem : Solar Orbiter observes a fully formed forward-reverse shock pair in the inner heliosphere

11/12/2024: High-energy insights from an escaping coronal mass ejection

04/12/2024: Investigation of Venus plasma tail using the Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe and Bepi Colombo flybys

27/11/2024: Testing the Flux Expansion Factor – Solar Wind Speed Relation with Solar Orbiter data

20/11/2024:The role of small scale EUV brightenings in the quiet Sun coronal heating

13/11/2024: Improved Insights from the Suprathermal Ion Spectrograph on Solar Orbiter

30/10/2024: Temporally resolved Type III solar radio bursts in the frequency range 3-13 MHz

23/10/2024: Resolving proton and alpha beams for improved understanding of plasma kinetics: SWA-PAS observations

25/09/2024: All microflares that accelerate electrons to high-energies are rooted in sunspots

25/09/2024: Connecting Solar Orbiter and L1 measurements of mesoscale solar wind structures to their coronal source using the Adapt-WSA model

18/09/2024: Modelling the global structure of a coronal mass ejection observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe

28/08/2024: Coordinated observations with the Swedish 1m Solar Telescope and Solar Orbiter

21/08/2024: Multi-source connectivity drives heliospheric solar wind variability

14/08/2024: Composition Mosaics from March 2022

19/06/2024: Coordinated Coronal and Heliospheric Observations During the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse

22/05/2024: Real time space weather prediction with Solar Orbiter

15/05/2024: Hard X ray and microwave pulsations: a signature of the flare energy release process

01/02/2024: Relativistic electrons accelerated by an interplanetary shock wave

11/01/2024: Modelling Two Consecutive Energetic Storm Particle Events observed by Solar Orbiter

2023

14/12/2023: Understanding STIX hard X-ray source motions using field extrapolations

16/11/2023: EUI data reveal a "steady" mode of coronal heating

09/11/2023: A new solution to the ambiguity problem

02/11/2023: Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe jointly take a step forward in understanding coronal heating

25/10/2023: Observations of mini coronal dimmings caused by small-scale eruptions in the quiet Sun

18/10/2023: Fleeting small-scale surface magnetic fields build the quiet-Sun corona

27/09/2023: Solar Orbiter reveals non-field-aligned solar wind proton beams and its role in wave growth activities

20/09/2023: Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops

23/08/2023: A sharp EUI and SPICE look into the EUV variability and fine-scale structure associated with coronal rain

02/08/2023: Solar Flare Hard Xrays from the anchor points of an eruptive filament

28/06/2023: 3He-rich solar energetic particle events observed close to the Sun on Solar Orbiter

14/06/2023: Observational Evidence of S-web Source of Slow Solar Wind

31/05/2023: An interesting interplanetary shock

24/05/2023: High-resolution imaging of coronal mass ejections from SoloHI

17/05/2023: Direct assessment of far-side helioseismology using SO/PHI magnetograms

10/05/2023: Measuring the nascent solar wind outflow velocities via the doppler dimming technique

26/04/2023: Imaging and spectroscopic observations of EUV brightenings using SPICE and EUI on board Solar Orbiter

19/04/2023: Hot X-ray onset observations in solar flares with Solar Orbiter/STIX

12/04/2023: Multi-scale structure and composition of ICME prominence material from the Solar Wind Analyser suite

22/03/2023: Langmuir waves associated with magnetic holes in the solar wind

15/03/2023: Radial dependence of the peak intensity of solar energetic electron events in the inner heliosphere

08/03/2023: New insights about EUV brightenings in the quiet sun corona from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

Sign in

Sign in

Science & Technology

Science & Technology