Science Nugget: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX - Solar Orbiter

First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

(Solar Orbiter Nugget #48 by Natália Bajnoková (1), Iain G. Hannah (1), Kristopher Cooper (2), Säm Krucker (3,4), Brian W. Grefenstette (5), David M. Smith (6), Natasha L. S. Jeffrey (7), Jessie Duncan (8))

1. Introduction

Hard X-rays (HXR) serve as an important diagnostic for plasma heating and particle acceleration [1]. Therefore, they are crucial for studying flare energy release processes, which are not fully understood. Microflares (GOES B class and smaller flares [2]) are good candidates for studying these processes as they occur more frequently and usually with simpler configurations than large flares. Two HXR instruments that have been observing microflares in recent years are NuSTAR [3] and Solar Orbiter/ STIX [4]. There are several advantages for conducting joint HXR microflare observations with NuSTAR and STIX:

- Combined observations of the same event from the two telescopes give us better constraint on the underlying physics of the energy release processes. This is especially important for events observed at limits of these instrument’s capabilities – in our case STIX has lower sensitivity than NuSTAR, but NuSTAR has limited throughput limiting observations of brighter events (due to effects like pile-up, where two or more photons are detected as a single photon).

- Observing the same flare from different angles allow us to probe the 3D structure of the flare, and if behind the limb from one viewpoint we can also simultaneously observe the faint coronal source and bright lower atmosphere footpoints [5].

In this work we present the first results of a simultaneous microflare observations with NuSTAR and STIX.

2. Overview of observations

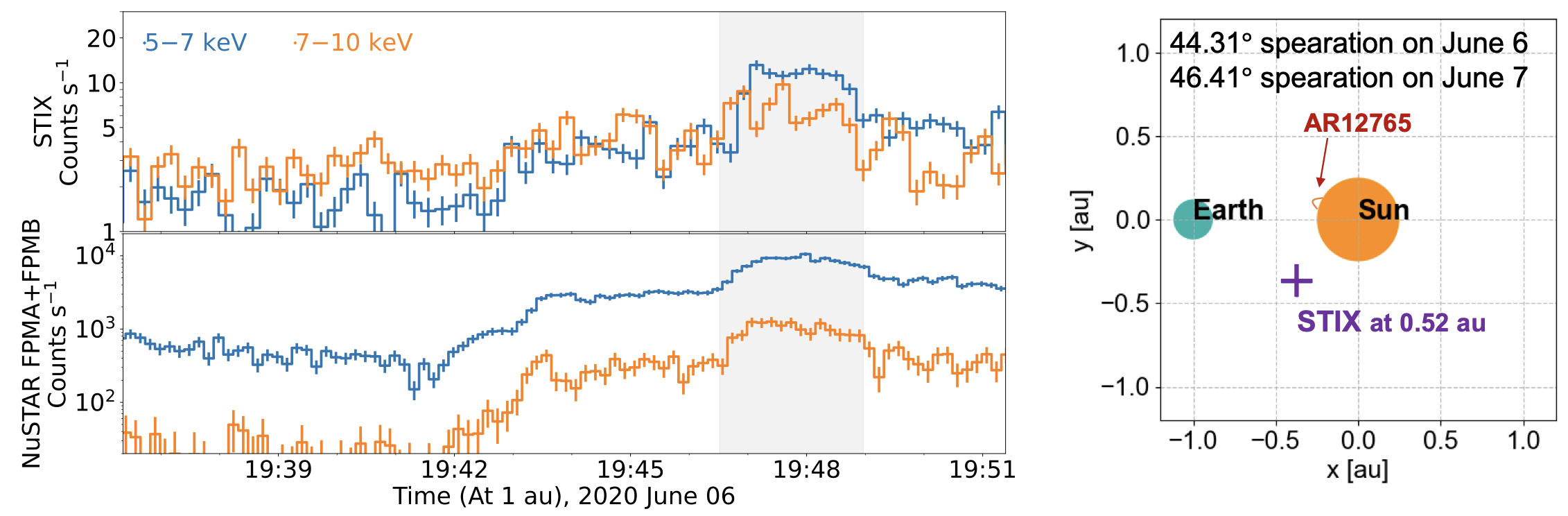

On 2020 June 6 and 7, NuSTAR and STIX jointly observed an active region AR12765 located close to the southeast solar limb. The instruments jointly observed 3 microflares (GOES B1, A7 and B6) that we divided into 5-time ranges over which we performed joint spectral fitting and imaging. During the observations the instruments were at approximately 45° separation (shown in the right panel in Figure 1) and both observed the microflares on-disk, thus observing the same X-ray sources. An example of STIX and NuSTAR lightcurves from a June 6 joint microflare are shown in the left panel in Figure 1.

Figure 1. (left) NuSTAR and STIX lightcurves from June 6 2020 GOES B1 class microflare. Region in grey highlights the even integration time. (right) The NuSTAR (Earth)–STIX–microflare AR positioning during the joint observations.

3. Joint spectral fitting and imaging

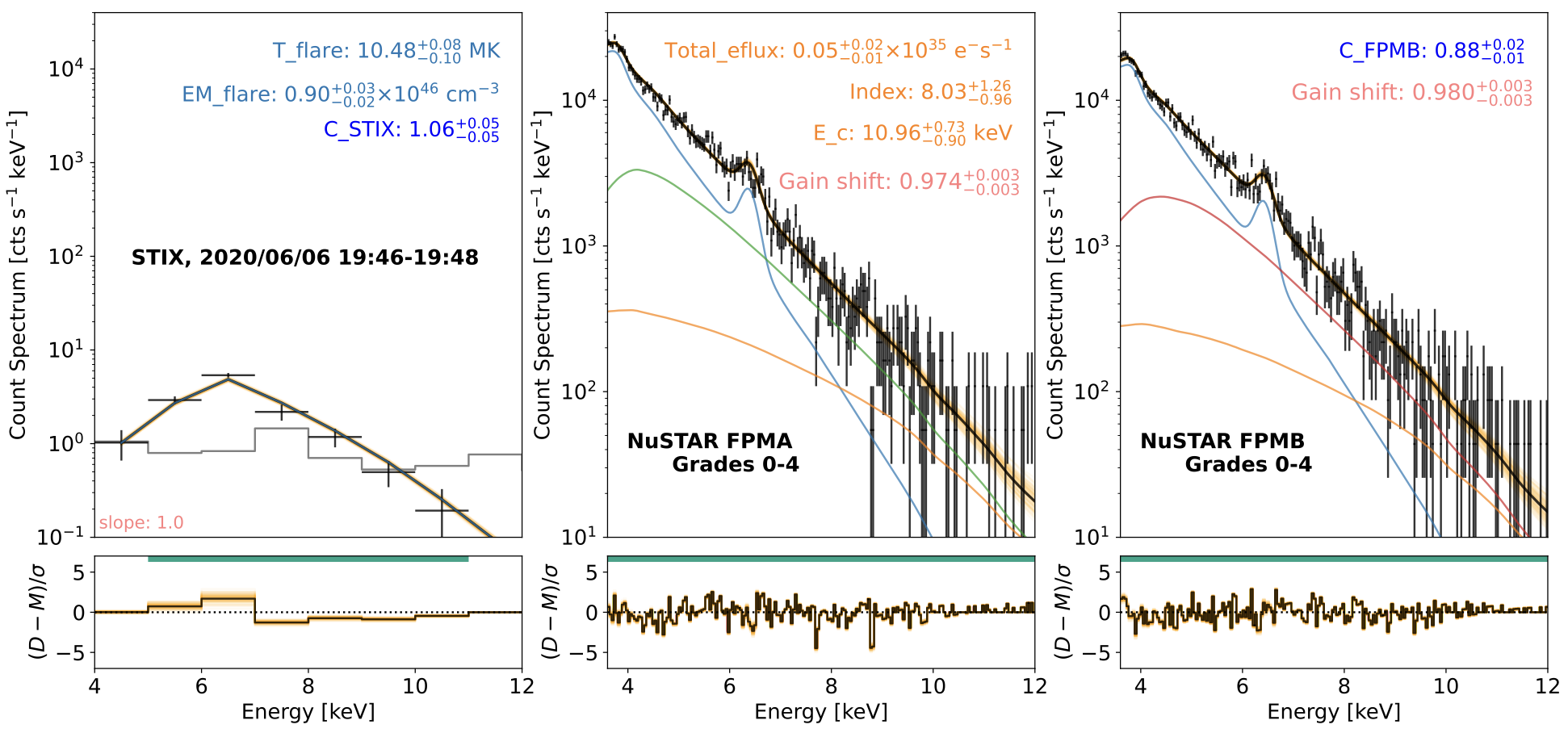

We have jointly fitted spectra from 5 different times from the 3 microflares using the new python X-ray fitting package sunkit-spex (https://github.com/sunpy/sunkit-spex). As NuSTAR contains two separate telescopes (FPMA and FPMB) this simultaneous fitting involves the two NuSTAR spectra and the STIX spectra, with added model scaling parameters to deal with small systematics between instruments. In addition, some of the microflares were bright enough to produce extremely low < 1% detector livetime in NuSTAR, meaning that that pile-up correction method had to be developed in sunkit-spex to model and fit this at the same time as the flare models.

An example of this joint spectral fitting is shown in Figure 2. In this case NuSTAR and STIX spectra were jointly fitted with a thermal model, with an additional non-thermal thick-target component to the NuSTAR spectra as it has more counts above background at higher energies. Despite the microflare being very faint for STIX and very bright for NuSTAR, consistent model parameters were found, which are in the expect range for HXR microflares [6]. In addition, the systematic differences between STIX and NuSTAR FPMA were only small, about 6%.

Figure 2. Example of joint spectral fitting for the June 6 microflare. NuSTAR contains two spectra from focal plane modules A and B that were pile-up corrected (the pile-up models are shown in green and red).

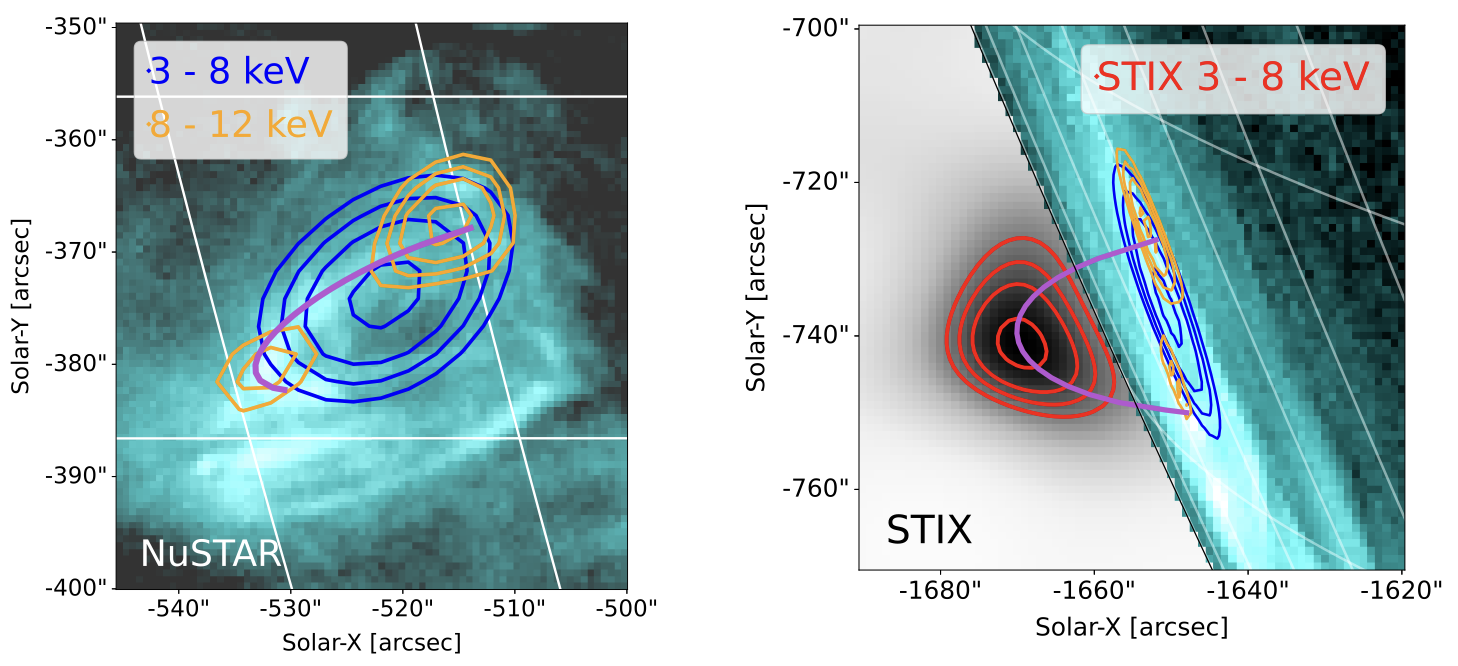

We were also able to perform joint imaging for this event. Images of NuSTAR and STIX HXR emission are shown overlain on 131 Å AIA images in Figure 3. With NuSTAR, we observed two non-thermal sources (orange) at either ends of an elongated thermal source (blue). This indicates the standard flare configuration consisting of non-thermal footpoints connected by hot flare loops. With STIX we were able to reconstruct a single lower energy (thermal) source originating from the hot flare loops (as suggested from the spectral fitting) that aligns well with the NuSTAR emission, reprojected to the STIX viewpoint.

Figure 3. Joint imaging for the June 6 microflare. The left panel shows NuSTAR image with 60, 70, 80 and 95% contour levels overlaid on a flare-time 131 Å SDO/AIA image. The right panel shows STIX image with matching contour levels to the NuSTAR ones as well as the reprojected NuSTAR contours.

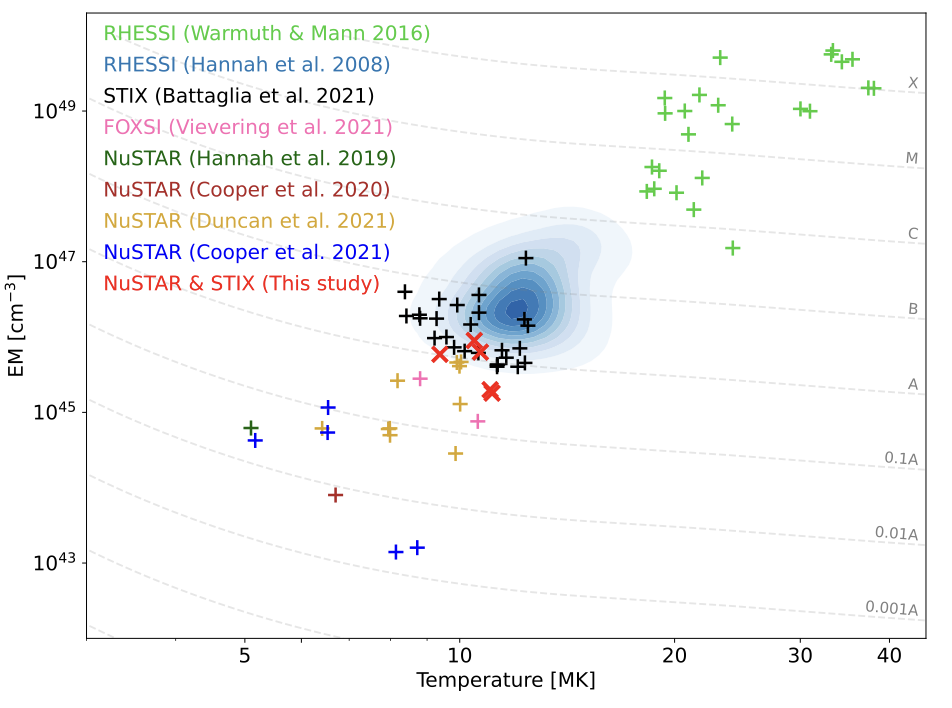

A similar analysis was performed on the other microflare, again finding consistent spectral fits and imaged structures STIX and NuSTAR. The thermal parameters found from the spectral fitting are shown in Figure 4, in the context of previous HXR microflare studies. These events clearly bridge the gap between previous NuSTAR and STIX studies.

Figure 4. Summary of temperature and emission measure parameters from various NuSTAR [7, 8, 9, 10], STIX [11], RHESSI [6, 12], and FOXSI [13] microflare and flare studies. The microflares from this study are marked as red crosses in bold.

4. Conclusions

We were able to successfully perform the first joint spectral and imaging analysis of microflares observed with NuSTAR and STIX. In the events studied we were able to get a reliable fit to the spectra, which might not have been possible individually as both instruments were operating at the limit of the capabilities. Work is ongoing, aiming for joint observations in more optimal conditions. The ideal NuSTAR–STIX configuration would be: a) Fainter GOES A class microflare observed during STIX perihelion (better sensitivity to faint emission) or b) GOES B class microflare observed as occulted for NuSTAR and on-disk for STIX which would allow us to detect the faint coronal energy release site with NuSTAR, and the resulting bright lower atmosphere emission with STIX.

This study has been published in Bajnoková, N., Hannah, I. G., Cooper, K., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 533, 3742, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stae2029162

Affiliations

(1) School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Glasgow, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK

(2) School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Minnesota Twin Cities, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

(3) School of Engineering, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, CH-5210 Windisch, Switzerland

(4) Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

(5) Cahill Center for Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, 1216 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

(6) Santa Cruz Institute of Particle Physics and Department of Physics, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA

(7) Department of Mathematics, Physics & Electrical Engineering, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST, UK

(8) NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, ST13, Huntsville, AL 35812, USA

References

[1] Benz A. O., 2017, Living Reviews in Solar Physics, 14, 2

[2] Hannah I. G., Hudson H. S., Battaglia M., Christe S., Kašparová J., Krucker S., Kundu M. R., Veronig A., 2011, Space Sci. Rev., 159, 263

[3] Harrison F. A., et al., 2013, ApJ, 770, 103

[4] Krucker S., et al., 2020, A&A, 642, A15

[5] Krucker S., Hurford G. J., Su Y., Gan W.-Q., 2019, Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics, 19, 167

[6] Hannah I. G., Christe S., Krucker S., Hurford G. J., Hudson H. S., Lin R. P., 2008, ApJ, 677, 704

[7] Hannah I. G., Kleint L., Krucker S., Grefenstette B. W., Glesener L., Hudson H. S., White S. M., Smith D. M., 2019, ApJ, 881, 109

[8] Cooper K., Hannah I. G., Grefenstette B. W., Glesener L., Krucker S., Hudson H. S., White S. M., Smith D. M., 2020, ApJ, 893, L40

[9] Duncan J., et al., 2021, ApJ, 908, 29

[10] Cooper K., et al., 2021, MNRAS, 507, 3936

[11] Battaglia A. F., et al., 2021, A&A, 656, A4

[12] Warmuth A., Mann G., 2016, A&A, 588, A115

[13] Vievering J. T., et al., 2021, ApJ, 913, 15

Nuggets archive

2025

19/03/2025: Radial dependence of solar energetic particle peak fluxes and fluences

12/03/2025: Analysis of solar eruptions deflecting in the low corona

05/03/2025: Propagation of particles inside a magnetic cloud: Solar Orbiter insights

19/02/2025: Rotation motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

12/02/2025: 'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

22/01/2025: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

15/01/2025: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

2024

18/12/2024: Shocks in tandem : Solar Orbiter observes a fully formed forward-reverse shock pair in the inner heliosphere

11/12/2024: High-energy insights from an escaping coronal mass ejection

04/12/2024: Investigation of Venus plasma tail using the Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe and Bepi Colombo flybys

27/11/2024: Testing the Flux Expansion Factor – Solar Wind Speed Relation with Solar Orbiter data

20/11/2024:The role of small scale EUV brightenings in the quiet Sun coronal heating

13/11/2024: Improved Insights from the Suprathermal Ion Spectrograph on Solar Orbiter

30/10/2024: Temporally resolved Type III solar radio bursts in the frequency range 3-13 MHz

23/10/2024: Resolving proton and alpha beams for improved understanding of plasma kinetics: SWA-PAS observations

25/09/2024: All microflares that accelerate electrons to high-energies are rooted in sunspots

25/09/2024: Connecting Solar Orbiter and L1 measurements of mesoscale solar wind structures to their coronal source using the Adapt-WSA model

18/09/2024: Modelling the global structure of a coronal mass ejection observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe

28/08/2024: Coordinated observations with the Swedish 1m Solar Telescope and Solar Orbiter

21/08/2024: Multi-source connectivity drives heliospheric solar wind variability

14/08/2024: Composition Mosaics from March 2022

19/06/2024: Coordinated Coronal and Heliospheric Observations During the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse

22/05/2024: Real time space weather prediction with Solar Orbiter

15/05/2024: Hard X ray and microwave pulsations: a signature of the flare energy release process

01/02/2024: Relativistic electrons accelerated by an interplanetary shock wave

11/01/2024: Modelling Two Consecutive Energetic Storm Particle Events observed by Solar Orbiter

2023

14/12/2023: Understanding STIX hard X-ray source motions using field extrapolations

16/11/2023: EUI data reveal a "steady" mode of coronal heating

09/11/2023: A new solution to the ambiguity problem

02/11/2023: Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe jointly take a step forward in understanding coronal heating

25/10/2023: Observations of mini coronal dimmings caused by small-scale eruptions in the quiet Sun

18/10/2023: Fleeting small-scale surface magnetic fields build the quiet-Sun corona

27/09/2023: Solar Orbiter reveals non-field-aligned solar wind proton beams and its role in wave growth activities

20/09/2023: Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops

23/08/2023: A sharp EUI and SPICE look into the EUV variability and fine-scale structure associated with coronal rain

02/08/2023: Solar Flare Hard Xrays from the anchor points of an eruptive filament

28/06/2023: 3He-rich solar energetic particle events observed close to the Sun on Solar Orbiter

14/06/2023: Observational Evidence of S-web Source of Slow Solar Wind

31/05/2023: An interesting interplanetary shock

24/05/2023: High-resolution imaging of coronal mass ejections from SoloHI

17/05/2023: Direct assessment of far-side helioseismology using SO/PHI magnetograms

10/05/2023: Measuring the nascent solar wind outflow velocities via the doppler dimming technique

26/04/2023: Imaging and spectroscopic observations of EUV brightenings using SPICE and EUI on board Solar Orbiter

19/04/2023: Hot X-ray onset observations in solar flares with Solar Orbiter/STIX

12/04/2023: Multi-scale structure and composition of ICME prominence material from the Solar Wind Analyser suite

22/03/2023: Langmuir waves associated with magnetic holes in the solar wind

15/03/2023: Radial dependence of the peak intensity of solar energetic electron events in the inner heliosphere

08/03/2023: New insights about EUV brightenings in the quiet sun corona from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

Sign in

Sign in

Science & Technology

Science & Technology