Science Nugget: Rotational motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan spine topology - Solar Orbiter

Rotational motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

(Solar Orbiter Nugget #51 by E. Petrova1 , T. Van Doorsselaere1, D. Berghmans2, S. Parenti3, G. Valori4, and J. Plowman5)

1. Introduction

Alfvén waves are of significant interest in the coronal heating problem due to their ability to transport energy from the lower layers of the Sun’s atmosphere to the corona [1]. However, their detection remains challenging because they are essentially rotational perturbations in plasma velocity and azimuthal components of the magnetic field, and are incompressible, and do not produce significant structural displacements [2]. As a result, they have primarily been observed using spectrometers across different layers of the solar atmosphere [4-8], while imaging instruments have struggled to capture them directly [3].

Recent advancements in solar imaging technology have drastically improved spatial and temporal resolution, enabling the detection of previously unresolved phenomena. In this study, we present new observations of propagating rotational motions within a fan-spine magnetic topology—a configuration consisting of a dome and a spine, formed when a magnetic bipole emerges into a preexisting unipolar field [9]. Numerical simulations suggest that this topology favours magnetic reconnection, which in turn generates propagating Alfvén waves [10-13]. Here, we use multiple instruments onboard Solar Orbiter to detect an event that has been extensively modelled in numerical studies.

2. Observational signatures of Alfvén waves

The images were obtained using three different instruments onboard Solar Orbiter: EUI/HRIEUV (174 Å channel, hereafter simply HRIEUV) for imaging observations, PHI for magnetic field data, and SPICE for spectral data (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the instrument’s FoVs as viewed from the Solar Orbiter FSI in 174 Å. Overlaid on top is the HRIEUV FoV, shown by red rectangle, and the SPICE and PHI FoVs are shown by blue and green rectangles, respectively.

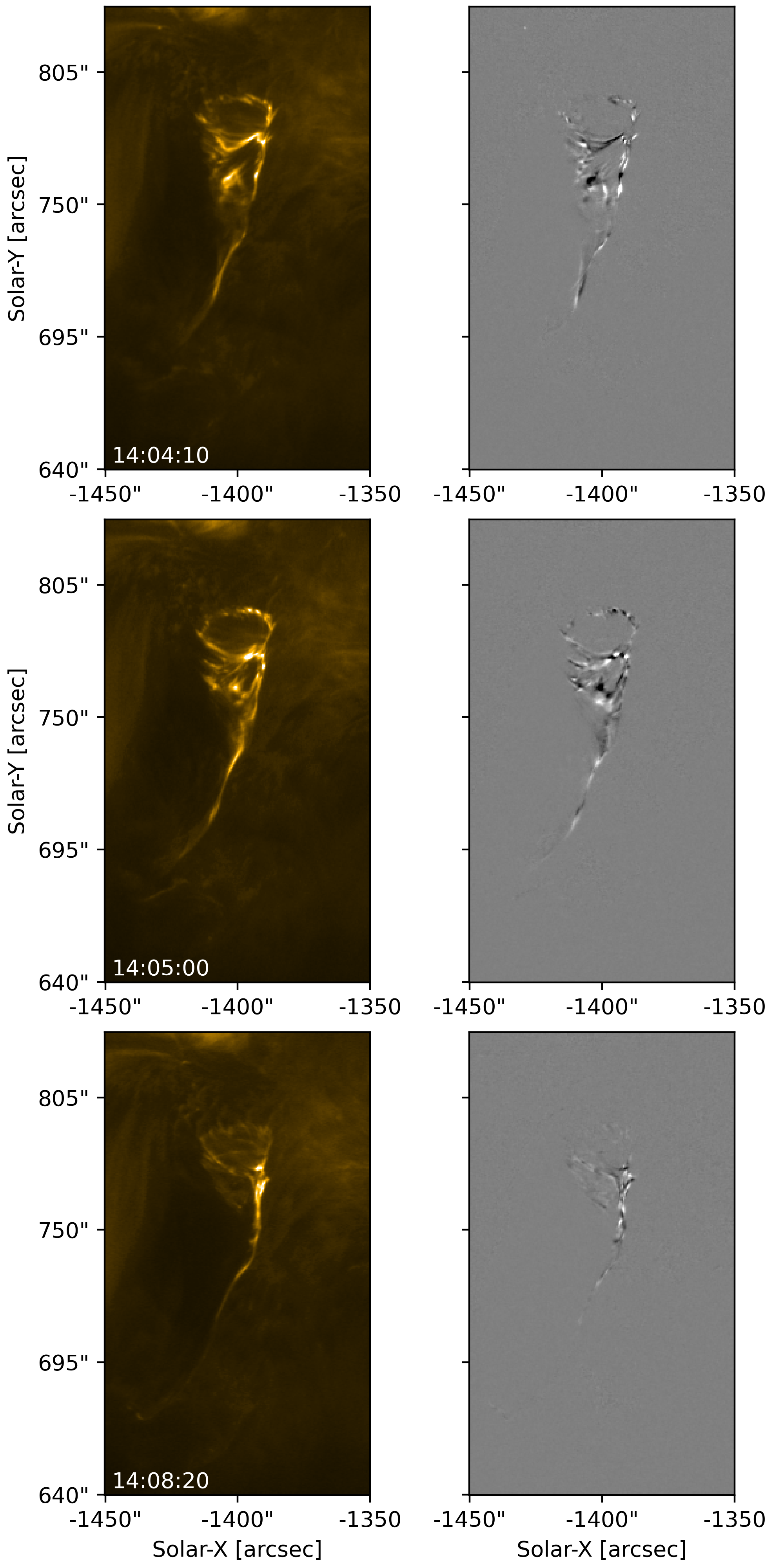

At the time, Solar Orbiter was near perihelion (at a distance of 0.32 AU from the Sun), and HRIEUV achieved a resolution of 100 × 100 km² with a temporal cadence of 5 seconds, allowing the detection of propagating pulses of rotational motion. The structure exhibiting these torsional motions consists of two footpoints connected by short loops and a 30 Mm-long spine originating from one footpoint (see Figure 2). A clear signature of torsional motions propagating along the spine is visible in both the original and difference images (the relative video showing the event's dynamics can be found here).

Figure 2. Sequence of images taken by HRIEUV. The left panel shows the original images and the right panel show a running difference images. A full movie can be found together with the full publication here.

Analysis of the time sequence reveals a southward longitudinal motion propagating at a speed consistent with local estimates of the Alfvén speed, ranging from approximately 130 to 180 km/s. Additionally, a transverse motion is observed with speeds of 26–56 km/s, constituting about 30% of the local Alfvén speed, suggesting a possible nonlinear regime. Given that SPICE data is available—and the Doppler velocity signal is typically the most compelling evidence for torsional Alfvén waves—we have also analysed the SPICE observations.

3. Doppler Velocity Analysis and Forward Modeling

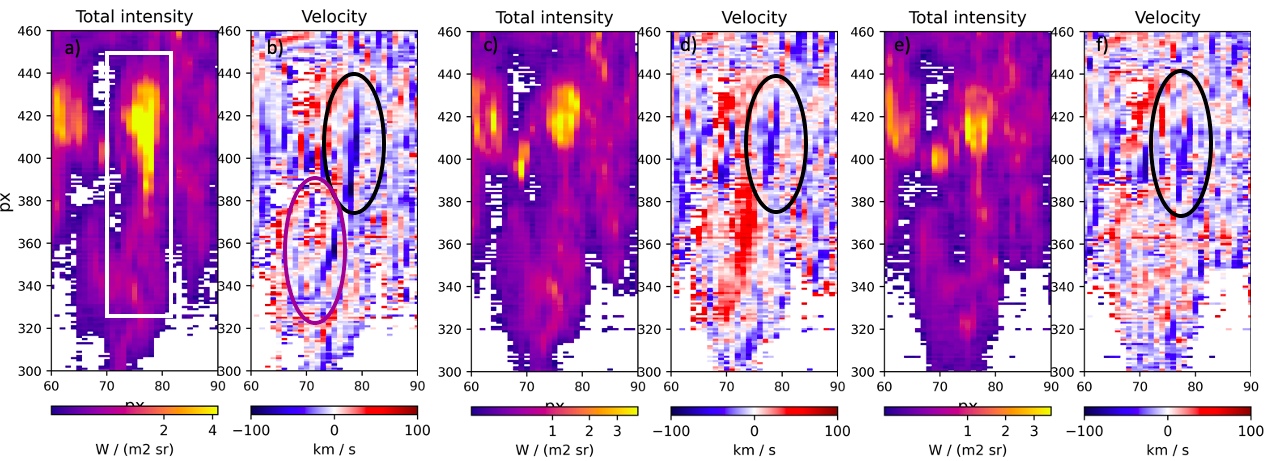

SPICE Doppler maps in the C III channel revealed strong signals in the spine region (see Figure 3), a characteristic signature of torsional Alfvén waves.

Figure 3. Intensity and Doppler maps obtained with the SPICE C III line for three time frames (14:02:59, 14:14:28, and 14:25:57). Panels a and b show maps for the first time frame, panels c and d are for the second, and panels e and f are for the last frame.

However there is an additional, non-physical source of signal in the Doppler maps—an artefact caused by the point spread function (PSF) of SPICE. The PSF is elongated in both the spectral and slit-aligned directions and tilted by approximately 15 degrees. This tilt in the spatial-spectral plane creates an illusionary dim feature adjacent to a bright feature, leading to artificial Doppler signals that follow intensity gradients. To accurately distinguish between physical and artificial signals, we performed forward-modelling analysis.

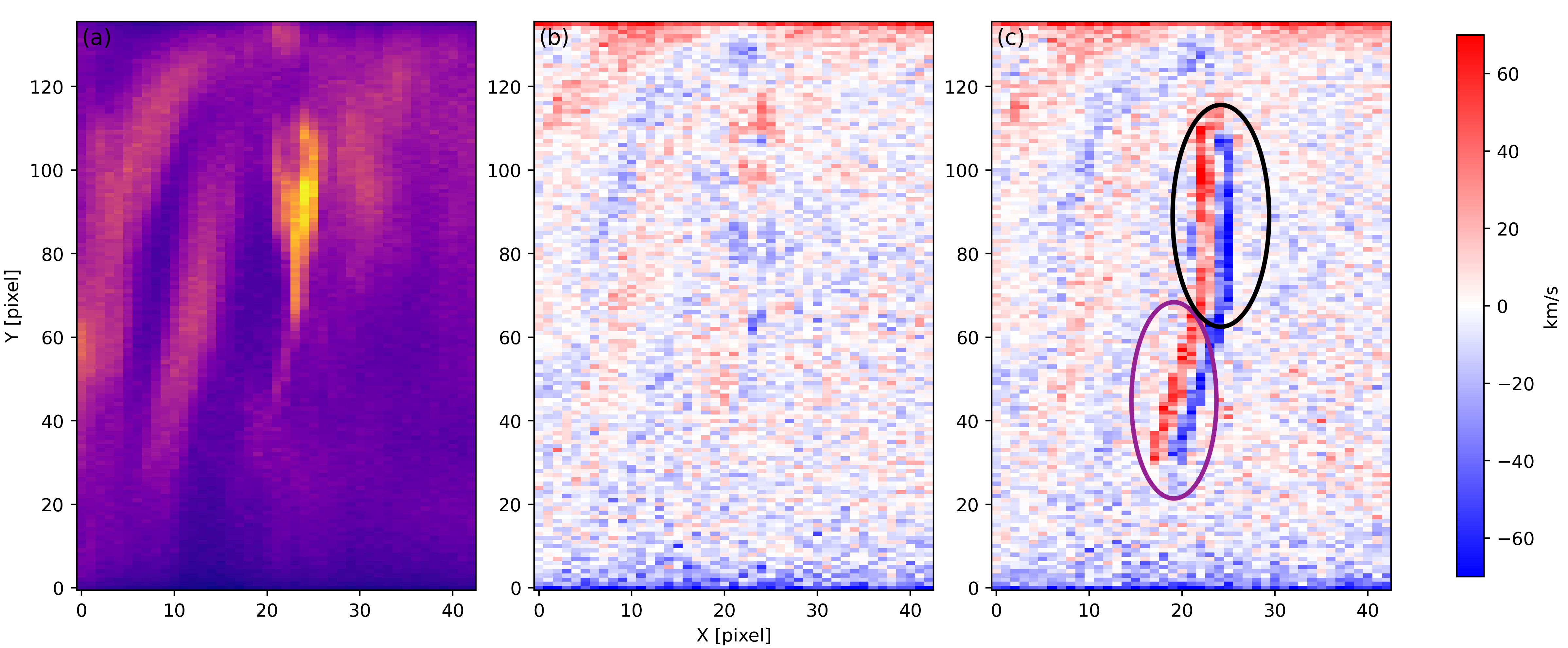

Using HRIEUV data as input, we recreated SPICE-like data to mimic the dataset. Two simulations were conducted: one incorporating only the PSF and another including both the PSF and imposed rotational motions modelled as the rigid body rotation. These simulations accounted for typical broadening sources, both thermal and non-thermal. The resulting intensity maps (see Figure 4(a)) closely resemble SPICE observations, particularly in the Ne VIII channel, which has a temperature response closest to the HRIEUV.

Figure 4. Synthesized spectral rasters obtained using forward-modelling analysis. Panel a shows the synthesized intensity, while the panels b and c show the Doppler maps (mimicking the SPICE CIII line) with and without local velocities imposed on top of the feature.

Panel (b) of Figure 4 confirms that a signal is present even without imposed motion, indicating that it arises purely from the PSF. However, panel (c) most closely resembles the SPICE data, suggesting that while the signal is modulated by the PSF—introducing various non-uniformities—it also contains strong blueshifts that align with SPICE observations. This alignment suggests that the detected signal is physical, assuming the recovered PSF is accurate.

Thus, the forward modelling provides additional support for interpreting the observed phenomenon as torsional motion, as it demonstrates the presence of a Doppler signal in the region corresponding to the spine.

4. Conclusions

Our study presents observational evidence of torsional Alfvén waves propagating within a coronal fan-spine magnetic topology. These findings provide crucial insights into the role of Alfvén waves in the solar atmosphere.

By leveraging high-resolution imaging from EUI and Doppler measurements from SPICE, we were able to confirm the presence of rotational motions along the spine structure. The synergy between different Solar Orbiter instruments has been pivotal in detecting these wave signatures, emphasising the importance of multi-instrument observations for understanding the Sun's dynamic plasma environment.

The ability of Alfvén waves to transport energy over large distances raises important questions about their role in coronal heating. If these waves contribute to energy redistribution, they could help sustain the high temperatures observed in the solar corona. Additionally, our findings highlight the potential for Alfvén waves to serve as diagnostics of the coronal magnetic field.

The full publication of this work can be found here: Petrova et al., A&A, 687, A13 (2024)

Affiliations

(1) Centre for mathematical Plasma Astrophysics, Mathematics Department, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200B Bus 2400, 3001 Leuven, Belgium

(2) Solar-Terrestrial Centre of Excellence - SIDC, Royal Observatory of Belgium, Ringlaan -3- Av. Circulaire, Brussels, 1180, Belgium

(3) Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, 91405 Orsay, France

(4) Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, Göttingen, Germany

(5) Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO 80302, USA

Acknowledgements

Solar Orbiter is a space mission of international collaboration between ESA and NASA, operated by ESA. The EUI instrument was built by CSL, IAS, MPS, MSSL/UCL, PMOD/WRC, ROB, LCF/IO with funding from the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO/PRODEX PEA 4000112292); the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES); the UK Space Agency (UKSA); the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) through the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR); and the Swiss Space Office (SSO). We are grateful to the ESA SOC and MOC teams for their support. The German contribution to SO/PHI is funded by the BMWi through DLR and by MPG central funds. The Spanish contribution is funded by AEI/MCIN/10.13039/501100011033/ and European Union “NextGenerationEU/PRTR” (RTI2018-096886-C5, PID2021- 125325OB-C5, PCI2022-135009-2, PCI2022-135029-2) and ERDF “A way of making Europe”; “Center of Excellence Severo Ochoa” awards to IAA- CSIC (SEV-2017-0709, CEX2021-001131-S); and a Ramón y Cajal fellowship awarded to DOS. The French contribution is funded by CNES. The development of SPICE has been funded by ESA member states and ESA. It was built and is operated by a multi-national consortium of research institutes supported by their respective funding agencies: STFCRAL (UKSA, hardwarelead), IAS (CNES, operationslead), GSFC (NASA), MPS (DLR), PMOD/WRC (SwissS- paceOffice), SwRI (NASA), UiO (NorwegianSpaceAgency). T.V.D. was supported by the C1 grant TRACEspace of Internal Funds KU Leuven. E.P. has benefited from the funding of the FWO Vlaanderen through a Senior Research Project (G088021N).

References

[1] Soler, R., Terradas, J., Oliver, R., & Ballester, J. L. 2019, ApJ, 871, 3

[2] Edwin, P. M., & Roberts, B. 1983, Sol. Phys., 88, 179

[3] Van Doorsselaere, T., Nakariakov, V. M., & Verwichte, E. 2008, ApJ, 676, L73

[4] Stangalini, M., Erdélyi, R., Boocock, C., et al. 2021, Nat. Astron., 5, 691

[5] Wedemeyer-Böhm, S., Scullion, E., Steiner, O., et al. 2012, Nature, 486, 505 Bohm

[6] Jess, D. B., Mathioudakis, M., Erdélyi, R., et al. 2009, Science, 323, 1582

[7] Srivastava, A. K., Shetye, J., Murawski, K., et al. 2017, Sci. Rep., 7, 43147

[8] Kohutova, P., Verwichte, E., & Froment, C. 2020, A&A, 633, L6

[9] Yang, S., Zhang, Q., Xu, Z., et al. 2020, ApJ, 898, 101

[10] Cirtain, J. W., Golub, L., Lundquist, L., et al. 2007, Science, 318, 1580

[11] Pariat, E., Antiochos, S. K., & DeVore, C. R. 2009, ApJ, 691, 61

[12] Török, T., Aulanier, G., Schmieder, B., Reeves, K. K., & Golub, L. 2009, ApJ,704, 485

[13] Pontin, D. I., Al-Hachami, A. K., & Galsgaard, K. 2011, A&A, 533, A78

Nuggets archive

2025

19/03/2025: Radial dependence of solar energetic particle peak fluxes and fluences

12/03/2025: Analysis of solar eruptions deflecting in the low corona

05/03/2025: Propagation of particles inside a magnetic cloud: Solar Orbiter insights

19/02/2025: Rotation motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

12/02/2025: 'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

22/01/2025: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

15/01/2025: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

2024

18/12/2024: Shocks in tandem : Solar Orbiter observes a fully formed forward-reverse shock pair in the inner heliosphere

11/12/2024: High-energy insights from an escaping coronal mass ejection

04/12/2024: Investigation of Venus plasma tail using the Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe and Bepi Colombo flybys

27/11/2024: Testing the Flux Expansion Factor – Solar Wind Speed Relation with Solar Orbiter data

20/11/2024:The role of small scale EUV brightenings in the quiet Sun coronal heating

13/11/2024: Improved Insights from the Suprathermal Ion Spectrograph on Solar Orbiter

30/10/2024: Temporally resolved Type III solar radio bursts in the frequency range 3-13 MHz

23/10/2024: Resolving proton and alpha beams for improved understanding of plasma kinetics: SWA-PAS observations

25/09/2024: All microflares that accelerate electrons to high-energies are rooted in sunspots

25/09/2024: Connecting Solar Orbiter and L1 measurements of mesoscale solar wind structures to their coronal source using the Adapt-WSA model

18/09/2024: Modelling the global structure of a coronal mass ejection observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe

28/08/2024: Coordinated observations with the Swedish 1m Solar Telescope and Solar Orbiter

21/08/2024: Multi-source connectivity drives heliospheric solar wind variability

14/08/2024: Composition Mosaics from March 2022

19/06/2024: Coordinated Coronal and Heliospheric Observations During the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse

22/05/2024: Real time space weather prediction with Solar Orbiter

15/05/2024: Hard X ray and microwave pulsations: a signature of the flare energy release process

01/02/2024: Relativistic electrons accelerated by an interplanetary shock wave

11/01/2024: Modelling Two Consecutive Energetic Storm Particle Events observed by Solar Orbiter

2023

14/12/2023: Understanding STIX hard X-ray source motions using field extrapolations

16/11/2023: EUI data reveal a "steady" mode of coronal heating

09/11/2023: A new solution to the ambiguity problem

02/11/2023: Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe jointly take a step forward in understanding coronal heating

25/10/2023: Observations of mini coronal dimmings caused by small-scale eruptions in the quiet Sun

18/10/2023: Fleeting small-scale surface magnetic fields build the quiet-Sun corona

27/09/2023: Solar Orbiter reveals non-field-aligned solar wind proton beams and its role in wave growth activities

20/09/2023: Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops

23/08/2023: A sharp EUI and SPICE look into the EUV variability and fine-scale structure associated with coronal rain

02/08/2023: Solar Flare Hard Xrays from the anchor points of an eruptive filament

28/06/2023: 3He-rich solar energetic particle events observed close to the Sun on Solar Orbiter

14/06/2023: Observational Evidence of S-web Source of Slow Solar Wind

31/05/2023: An interesting interplanetary shock

24/05/2023: High-resolution imaging of coronal mass ejections from SoloHI

17/05/2023: Direct assessment of far-side helioseismology using SO/PHI magnetograms

10/05/2023: Measuring the nascent solar wind outflow velocities via the doppler dimming technique

26/04/2023: Imaging and spectroscopic observations of EUV brightenings using SPICE and EUI on board Solar Orbiter

19/04/2023: Hot X-ray onset observations in solar flares with Solar Orbiter/STIX

12/04/2023: Multi-scale structure and composition of ICME prominence material from the Solar Wind Analyser suite

22/03/2023: Langmuir waves associated with magnetic holes in the solar wind

15/03/2023: Radial dependence of the peak intensity of solar energetic electron events in the inner heliosphere

08/03/2023: New insights about EUV brightenings in the quiet sun corona from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

Sign in

Sign in

Science & Technology

Science & Technology