Science Nugget: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two vantage points - Solar Orbiter

Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

(Solar Orbiter Nugget #49 by Takayoshi Oba1,*, Luis R. Bellot Rubio2, Daniele Calchetti1, Johann Hirzberger1, Sami K. Solanki1, Yukio Katsukawa3)

1. Introduction

The quiet solar photosphere exhibits a cellular pattern based on bright granules which are surrounded by dark channels called intergranular lanes [1]. A granule is the manifestation of an overshooting hot upflow from the convective unstable subsurface layers into the stable photosphere. This vigorous convective process gives rise to dynamical phenomena such as exploding granules [2], supersonic flows [3], vortex tubes [4], and reversed granulation [5]. In addition, the gas convection plays a major role in structuring the chromosphere and the corona, by converting kinetic energy into magnetic energy through flux tubes that extend into these upper atmospheric layers. To understand these phenomena, numerous studies have been conducted to characterize the gas convection in the solar surface.

One of the key physical quantities for understanding these phenomena is the horizontal gas flow on the solar surface, as all the aforementioned phenomena are closely associated with it. However, deriving this physical quantity is quite challenging. Since Doppler shift measurements provide the velocity of gas motion along the line-of-sight (LOS), a straightforward approach might use observations near the solar limb, where the LOS reflects horizontal motion. However, foreshortening effects considerably degrades the effective spatial resolution. A promising approach is to take advantage of the stereoscopic observation. The joint use of the Solar Orbiter / Polarimetric Helioseismic Imager (SO/PHI) [6] and Hinode/Solar Optical Telescope-Spectropolarimeter (SOT/SP) [7] is particularly well-suited for studying the small-scale feature, such as the granulation, thanks to their stable observations from space and their comparable high spatial resolution. This article introduces how these instruments, observing from different viewing angles, provide a novel approach to study the solar granulation and its related velocity fields.

2. Data and coalignment

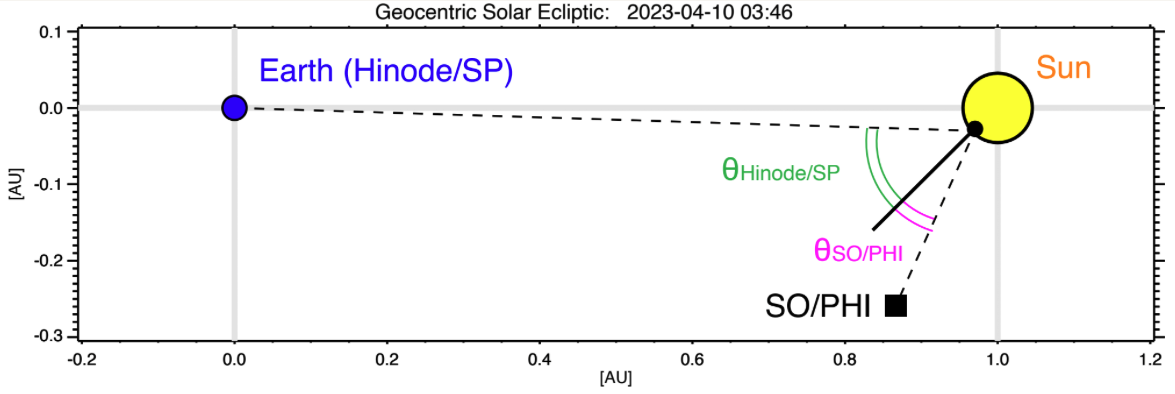

Both Hinode/SP and SO/PHI provide spectropolarimetric observations of photospheric absorption lines. While Hinode/SP employs a slit-based system, SO/PHI is based on a tunable filtergraph. Both instruments are able to retrieve the LOS velocity by Doppler shifts from their spectral line. The target is a quiet region observed on 10th April 2023. During the observational campaign, SO/PHI-HRT (high resolution telescope) took spectral scans over a period of 6 hours with a 1-minute cadence, while Hinode/SP repeatedly rastered a large field-of-view. The observation location was near the solar equator, positioned off disk-center for both instruments. The heliocentric angles, expressed as cosθ (where θ is the deviation of the LOS of the observer from the surface normal at the observation point), were 0.8 for Hinode and 0.9 for Solar Orbiter (Fig. 1). The separation angle between the Sun-Hinode and the Sun-SO lines was 63 degrees.

Since the granulation pattern is an extremely small-scale phenomenon, precise coalignment is essential. Several challenges must be addressed, including differences in pixel sampling, image distortion, viewing angles, and even observation systems (i.e., slit-based vs. filtergraph). In our coalignment approach, scaling and offsets in the x- and y-directions are determined through the affine transformation to maximize the correlation [8]. In addition, Hinode/SP’s slit-scan system rasters the spatial region step by step, while the granulation evolves on relatively short timescales. To address this, temporal interpolation is applied to a time series of the SO/PHI snapshots. This ensures that any pixel in the resulting SO/PHI composite map corresponds to the same observation time as Hinode/SP at each slit position.

Figure 1. Spatial relation among Earth (Hinode), the Sun, and Solar Orbiter in the Geocentric Solar Ecliptic coordinate system at the observation time of 10th April 2023. θHinode/SP is the heliocentric angle for the Hinode/SP observation, whereas θSO/PHI is the heliocentric angle for the SO/PHI observation.

3. Results

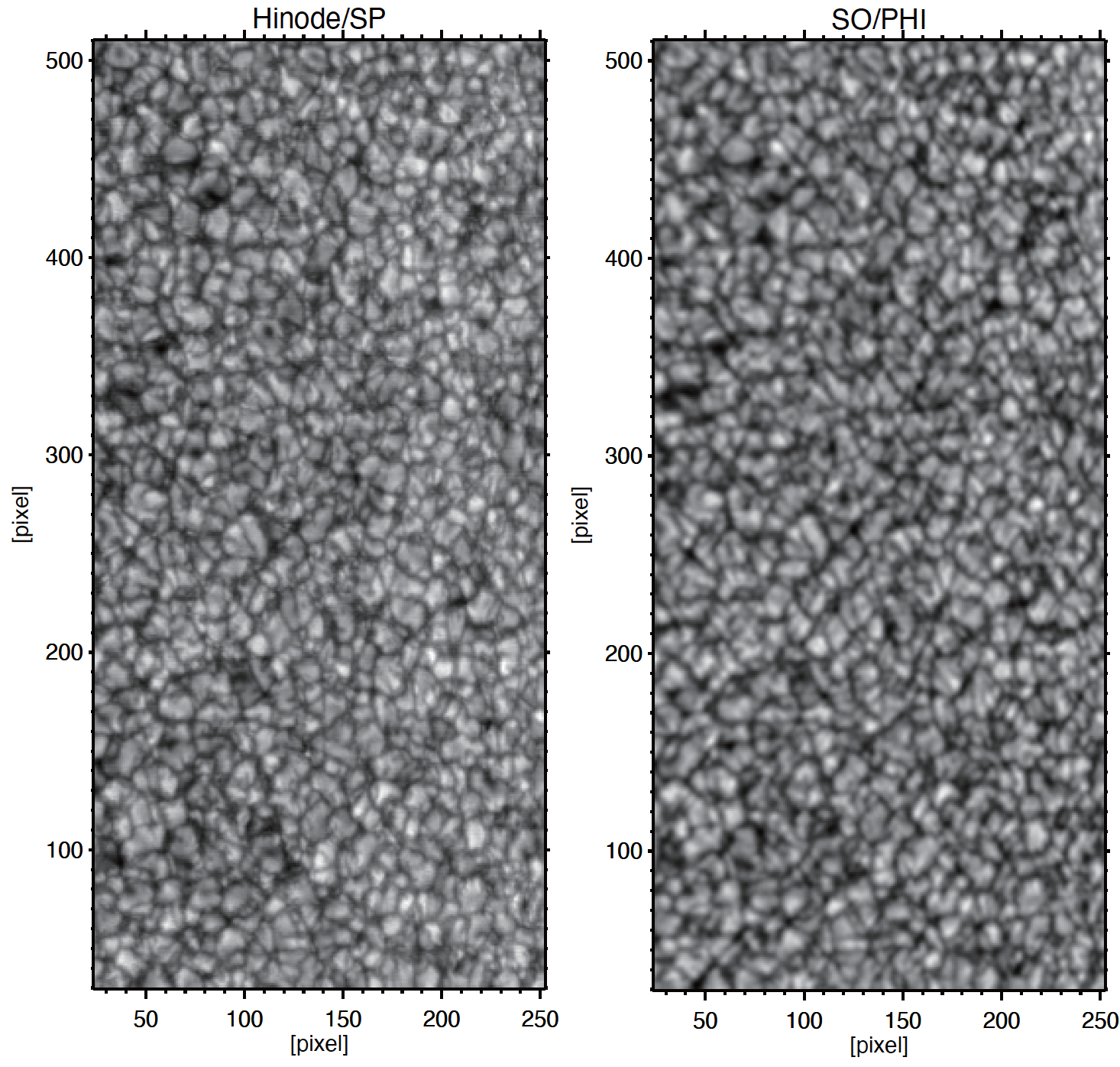

Figure 2 shows the intensity maps from Hinode/SP (left panel) and SO/PHI (right panel). It should be noted that the two maps are composed of the same number of spatial pixels in the x and y directions, enabling a direct one-to-one pixel comparison. The two intensity images exhibit a strong correspondence with a correlation coefficient of 0.91. While the intensity contrasts are comparable, the Hinode/SP map appears slightly sharper.

Figure 2. Continuum intensity map from Hinode/SP. Right: Composite continuum intensity map derived from a time series of the SO/PHI observations.

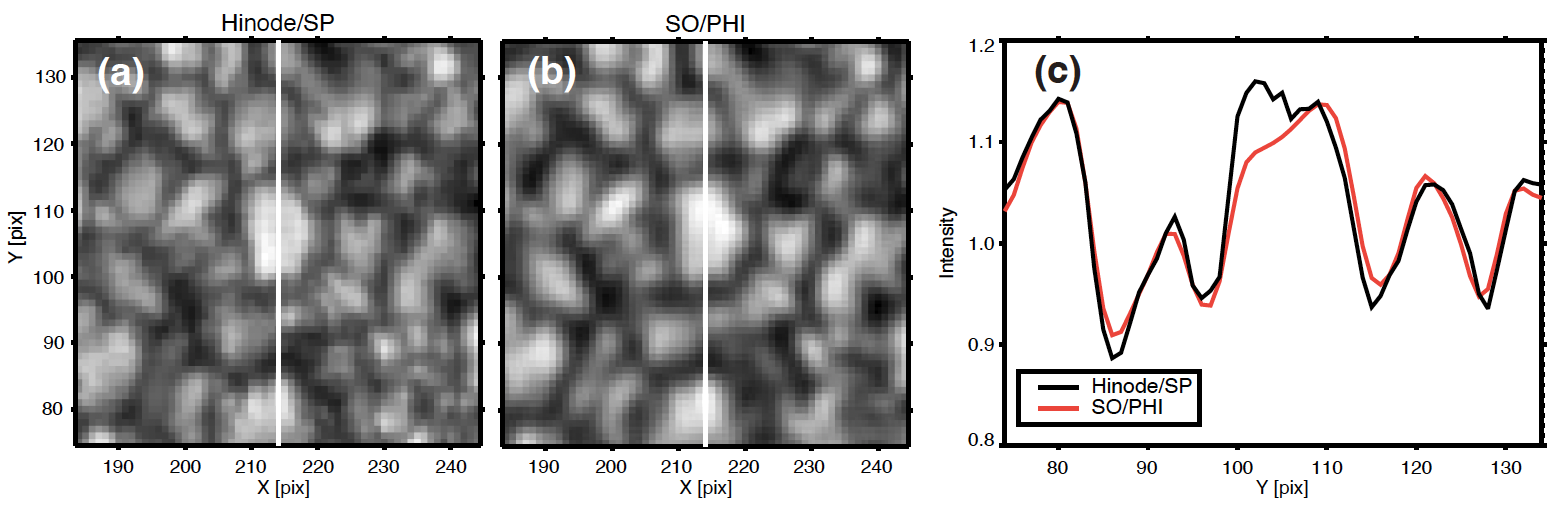

Figure 3 (a) and (b) provide enlarged views for a detailed comparison between the two images. While the overall correspondence is good, residual difference can be seen, particularly in regions with large granules. This discrepancy is more discernible in Fig.3 (c), which illustrates the intensity profiles along a slice cutting through a large granule. These observed discrepancies are likely due to the opacity effect: in the photosphere, opacity is primarily temperature-dependent [9], i.e., a granule with hot-material creates a hill whereas an intergranular lane with cool-material creates a valley [10], resulting in the different heights or locations being sampled by the two instruments with different viewing angles. Further investigation is needed to better understand the origins of these discrepancies.

Figure 3. Panel (a): Intensity map of Hinode/SP. Panel (b): Composite intensity map derived from the SO/PHI observations. Panel (c): Intensity profile from Hinode/SP (black) and SO/PHI (red), at the central position marked with the vertical white lines in panels (a) and (b).

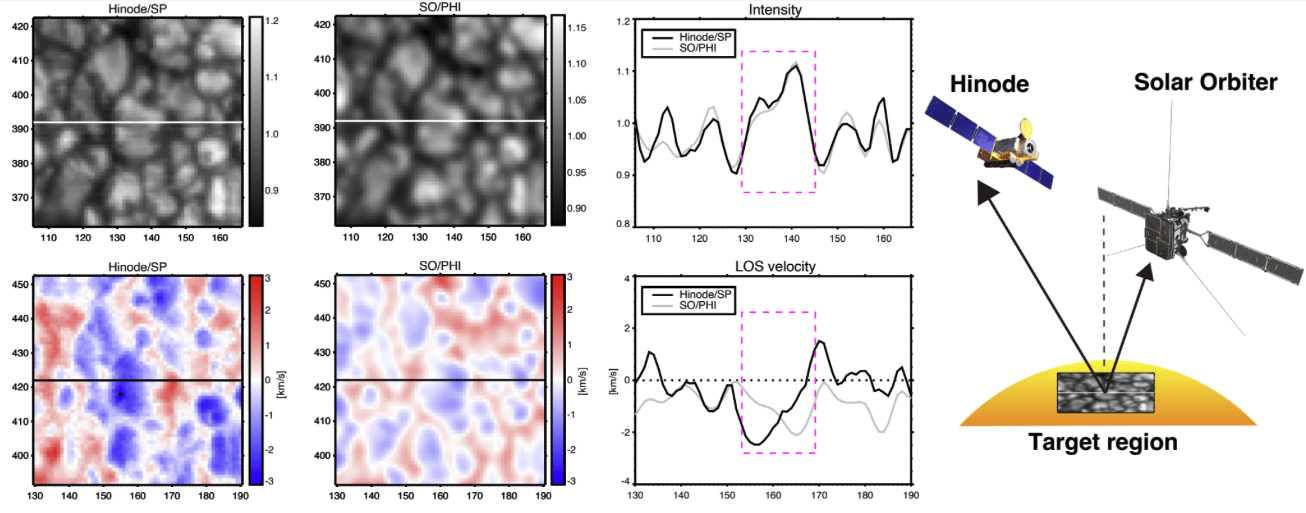

Figure 4 provides another closer view of the intensity maps (top row) and the LOS velocity (bottom row). It is evident from the two LOS velocity maps that SO/PHI sees smaller velocities than Hinode/SP, as the same color scale is applied to both maps. Several factors contribute to this difference. First, SO/PHI has slightly lower spatial resolution compared to Hinode/SP, as indicated by a bit sharper intensity image of Hinode/SP. Second, the different sensitivity to vertical and horizontal flow fields according to their respective heliocentric angle. With cos θHinode/SP = 0.8 for Hinode/SP, it is more sensitive to the horizontal flow than cos θSO/PHI=0.9 for SO/PHI, resulting in faster LOS velocity since the horizontal flow is expected to be approximately twice as fast as vertical flow [11][12]. Additionally, instrumental differences, such as the limited number of wavelength samples in SO/PHI, further contribute to the discrepancy in the amplitude of the LOS velocity.

Figure 4. Top row: Intensity maps from Hinode/SP and SO/PHI, along with their intensity profiles at the central location, from left to right, respectively. Bottom raw: Same as the top row, but for LOS velocity field. Note that the left side is the viewing direction from Hinode/SP whereas the right side is that from SO/PHI, as illustrated by the right most cartoon that describes the geometric configuration of Hinode/SP and SO/PHI with respect to the observational target region.

Although several issues still remain to be addressed for a direct comparison of the two LOS velocity maps, one implication regarding the general properties of the gas convection can be readily drawn. An illustrative example is highlightened by the magenta dashed rectangular boxes in the right column. The LOS velocity map of Hinode/SP shows a strong blue shift on the left side of the granule (toward the disk center), whereas the right side (toward the limb) exhibits a red shift. In contrast, the LOS velocity map of SO/PHI shows that the left side (toward the limb for SO/PHI) displays a red shift or weak blue shift, whereas the right side (toward the disk center for SO/PHI) shows strong blue shift. The right most cartoon should serve as a helpful reference for understanding the geometric configuration. These findings suggest that the granule exhibits a fountain-like divergent flow. This behavior is naturally expected from convection theory, but this result represents the first ever direct observational confirmation using Doppler measurements.

4. Conclusions

Hitherto, only one of the three components of the photospheric velocity vector could be obtained. Deriving the full velocity vector is essential to characterize the dynamical behaviors seen in the solar atmospheres. Our coalignment approach allows a direct comparison of both instruments with different viewing angles. The comparison of the coaligned LOS velocity maps clearly reveals the presence of a divergent flow in a granule, as predicted from convection theory.

The next step is to derive 2 of the 3 components of the velocity field in the photosphere. This process requires decomposition of the two LOS velocity fields into the vertical and horizontal flows, taking into account of the heliocentric angle for both instruments. The spatial distribution of the velocity field vectors can characterize an act of divergence/compression and shear/rotation in the gas convection. This valuable information offers insights into how convection drives dynamical phenomena, acts on magnetic flux tubes, and connects to the upper solar atmospheres.

Affiliations

(1) Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, Justus-von-Liebig-Weg 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany. *email: oba@mps.mpg.de

(2) Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC), Apartado de Correos 3004, E-18080 Granada, Spain

(3) National Astronomical observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa, Mitaka, Tokyo 181-8588, Japan

References

[1] Stix, M. 2002, The Sun: An Introduction, 2nd ed. (Berlin: Springer)

[2] Hirzberger, J., et al., 1999, ApJ, 527, 405, doi: 10.1086/308065

[3] Steiner, O., et al., 2010, ApJ, 723, L180, doi: 10.1088/2041-8205/723/2/L180

[4] Cheung, M. C. M., Schüssler, M., & Moreno-Insertis, F. 2007, A&A, 461, 1163, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20066390

[5] Bellot Rubio, L. R. 2009, ApJ, 700, 284, doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/700/1/284

[6] Solanki, S. K., del Toro Iniesta, J. C., Woch, J., et al. 2020, A&A, 642, A11, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201935325

[7] Tsuneta, S., et al., 2008, Solar physics, Volume 249, Issue 2, pp.167-196, doi: 10.1007/s11207-008-9174-z

[8] Fouhey, D. F., Higgins, R. E. L., Antiochos, S. K., et al. 178 2023, ApJS, 264, 49, doi: 10.3847/1538-4365/aca539

[9] Gray, D. F. 2008, in The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres, ed. D. F. Gray (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press)

[10] Balthasar, H. 1985, SoPh, 99, 31, doi: 10.1007/BF00157296

[11] Nesis, A., & Mattig, W. 1989, A&A, 221, 130, doi: 10.1051/0004-6361:20010464

[12] Oba, T., et al., 2020, ApJ, 890, 141, doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/ab6a90

Nuggets archive

2025

19/03/2025: Radial dependence of solar energetic particle peak fluxes and fluences

12/03/2025: Analysis of solar eruptions deflecting in the low corona

05/03/2025: Propagation of particles inside a magnetic cloud: Solar Orbiter insights

19/02/2025: Rotation motions and signatures of the Alfvén waves in a fan-spine topology

12/02/2025: 'Sun'day everyday: 2 years of Solar Orbiter science nuggets that shed light on some of our star's mysteries

22/01/2025: Velocity field in the solar granulation from two-vantage points

15/01/2025: First joint X-ray solar microflare observations with NuSTAR and Solar Orbiter/STIX

2024

18/12/2024: Shocks in tandem : Solar Orbiter observes a fully formed forward-reverse shock pair in the inner heliosphere

11/12/2024: High-energy insights from an escaping coronal mass ejection

04/12/2024: Investigation of Venus plasma tail using the Solar Orbiter, Parker Solar Probe and Bepi Colombo flybys

27/11/2024: Testing the Flux Expansion Factor – Solar Wind Speed Relation with Solar Orbiter data

20/11/2024:The role of small scale EUV brightenings in the quiet Sun coronal heating

13/11/2024: Improved Insights from the Suprathermal Ion Spectrograph on Solar Orbiter

30/10/2024: Temporally resolved Type III solar radio bursts in the frequency range 3-13 MHz

23/10/2024: Resolving proton and alpha beams for improved understanding of plasma kinetics: SWA-PAS observations

25/09/2024: All microflares that accelerate electrons to high-energies are rooted in sunspots

25/09/2024: Connecting Solar Orbiter and L1 measurements of mesoscale solar wind structures to their coronal source using the Adapt-WSA model

18/09/2024: Modelling the global structure of a coronal mass ejection observed by Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe

28/08/2024: Coordinated observations with the Swedish 1m Solar Telescope and Solar Orbiter

21/08/2024: Multi-source connectivity drives heliospheric solar wind variability

14/08/2024: Composition Mosaics from March 2022

19/06/2024: Coordinated Coronal and Heliospheric Observations During the 2024 Total Solar Eclipse

22/05/2024: Real time space weather prediction with Solar Orbiter

15/05/2024: Hard X ray and microwave pulsations: a signature of the flare energy release process

01/02/2024: Relativistic electrons accelerated by an interplanetary shock wave

11/01/2024: Modelling Two Consecutive Energetic Storm Particle Events observed by Solar Orbiter

2023

14/12/2023: Understanding STIX hard X-ray source motions using field extrapolations

16/11/2023: EUI data reveal a "steady" mode of coronal heating

09/11/2023: A new solution to the ambiguity problem

02/11/2023: Solar Orbiter and Parker Solar Probe jointly take a step forward in understanding coronal heating

25/10/2023: Observations of mini coronal dimmings caused by small-scale eruptions in the quiet Sun

18/10/2023: Fleeting small-scale surface magnetic fields build the quiet-Sun corona

27/09/2023: Solar Orbiter reveals non-field-aligned solar wind proton beams and its role in wave growth activities

20/09/2023: Polarisation of decayless kink oscillations of solar coronal loops

23/08/2023: A sharp EUI and SPICE look into the EUV variability and fine-scale structure associated with coronal rain

02/08/2023: Solar Flare Hard Xrays from the anchor points of an eruptive filament

28/06/2023: 3He-rich solar energetic particle events observed close to the Sun on Solar Orbiter

14/06/2023: Observational Evidence of S-web Source of Slow Solar Wind

31/05/2023: An interesting interplanetary shock

24/05/2023: High-resolution imaging of coronal mass ejections from SoloHI

17/05/2023: Direct assessment of far-side helioseismology using SO/PHI magnetograms

10/05/2023: Measuring the nascent solar wind outflow velocities via the doppler dimming technique

26/04/2023: Imaging and spectroscopic observations of EUV brightenings using SPICE and EUI on board Solar Orbiter

19/04/2023: Hot X-ray onset observations in solar flares with Solar Orbiter/STIX

12/04/2023: Multi-scale structure and composition of ICME prominence material from the Solar Wind Analyser suite

22/03/2023: Langmuir waves associated with magnetic holes in the solar wind

15/03/2023: Radial dependence of the peak intensity of solar energetic electron events in the inner heliosphere

08/03/2023: New insights about EUV brightenings in the quiet sun corona from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager

Sign in

Sign in

Science & Technology

Science & Technology